Most airport bookstores don’t carry Will Hagle‘s book, but that’s okay because he leaves free signed copies in airport bathrooms.

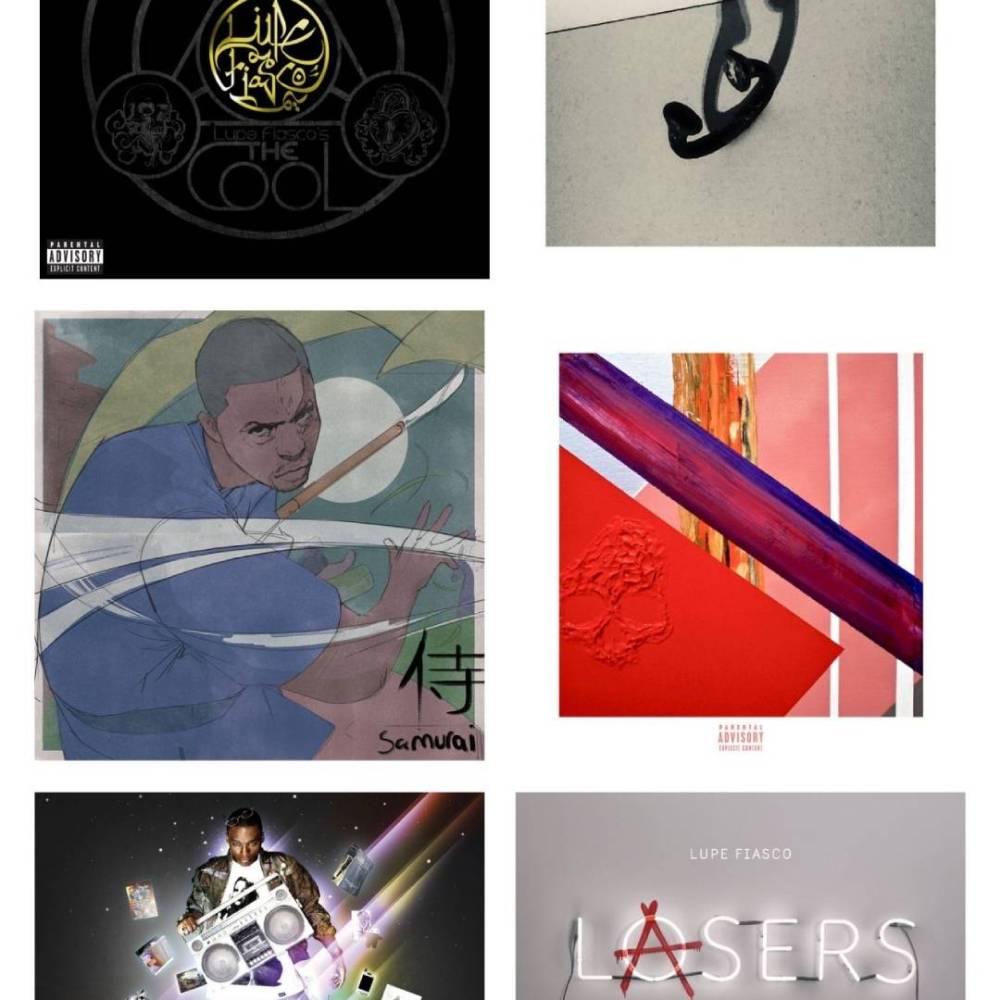

Across nine studio albums, Lupe Fiasco’s discography has been worshipped and mocked, vigilantly dissected and occasionally overlooked. He’s earned platinum plaques and Grammy nominations and still remains ignored by 96 percent of the population every time he drops. The other 4 percent treat it like holy scripture.

After 20 years in the game, the mixtape “lyrical savior” from the Revenge of the Nerds era has become a 42-year old vet – an underground-minded artist with a following big enough to get Coachella bookings. The Chicago rapper’s cultural relevance has faded and re-emerged several times since his breakout verse on Late Registration’s “Touch the Sky.” His longtime diehards have aged with him while many younger fans believe Tetsuo & Youth to be “the one.”

In 2024, it can be hard for the casual “Kick Push” listener of yesteryear to feel excited about a new Lupe LP. Not even Nas, a consensus Top 5 rapper, is immune from this condition. Career longevity is difficult and sustaining enthusiasm even harder. Mass opinion often holds that Lupe fell off after Lasers, but he’s just gained greater creative freedom. In his elder years, removed from the spotlight, he’s become more of a niche cult hero than a superstar. It better suits his sensibilities.

If you aren’t a Lupe acolyte, you may not know that he has a new album out. Samurai features production exclusively from longtime collaborator Soundtrakk. It may be difficult to convince you to feel excitement about it, but I can guarantee that if you enjoyed Lupe Fiasco’s music at any point in your life, it will offer a pleasurable listening experience. By the end of this list, I hope I’ll have persuaded you that it’s Lupe’s [SPOILER] album ever.

Regardless of the critical and commercial reactions, Lupe has steadfastly designed each album as a complete audio experience. He makes conceptual albums with the Kendrick’s ambition, and his lyrical and technical ability comes from the same lineage – albeit with a heavy Chicago influence. He employs third-person storytelling without (mostly) being overwrought. He favors high-concept thematic structures that often connect in loose threads from one LP to the next. His focus on the eternal tug between good and evil began with Food & Liquor and always finds its way to the forefront in some fashion.

Because it made sense at the time, I decided to relisten to every Lupe Fiasco album in order to come up with my own Definitive Rankings. In the process, a theme of my own emerged: every new Lupe LP is, to me, his best ever. This could be recency bias, but it’s also the mark of great artistry. Lupe has sustained a double-decade career not because his style is timeless, but because he shifts and adapts to present listeners the styles they want or need to hear at certain times.

Without further adieu, a ranking each of his albums from worst to best.

DROGAS Light is Lupe’s Untitled, Unmastered. It’s the least cohesive, least thematic, and least narrative-based album. There’s no hit. It doesn’t sound as polished. Lupe admitted that many of the songs were older recordings. For a rapper of Lupe’s caliber, the bar is high, and he’s never fit into the mixtape or playlist eras. He’s an album artist. DROGAS Light is technically an album, and it’s not bad, but it’s Lupe’s worst.

The best part of the album is “Tranquillo,” largely because of Rick Ross and Big K.R.I.T.’s verses. Big K.R.I.T., by the way, is another artist whose career is analogous to Lupe’s. He’s never reached the mainstream success he deserves, but those who’ve continued to stay tuned in have reaped plenty of dividends.

After the relative critical bomb of Lasers, Lupe reverted to the old tried and true fan service tactic: a sequel. The album cover was completely blank, which he’d later claim was a way to test Atlantic Records. His relationship with the label had been tenuous since the start, but Food & Liquor II wasn’t merely a throwaway record to fulfill contract obligations. If you put it on without prior context, it has a few enjoyable songs. But Lasers irrevocably altered the way that audiences perceived Lupe. Reusing the Food & Liquor title wasn’t the right choice to dig him out of that hole.

If this album had any other name, it might have been more well-received. Sequels are almost always disappointing. Lupe raps about the same Manichean struggles on every album, but calling this one Food & Liquor again set it up for failure. Before Anchorman 2, Will Ferrell had never acted in a sequel. He was on a hit streak until he did that. There’s a lesson to be learned here.

Drill Music in Zion was much more critically acclaimed than Lasers, but I didn’t really like it and I haven’t listened to it enough to defend my opinion. I understand what the album is supposed to be about, but it’s too long and slow for me. Soundtrakk produced every track here, too. The production choices suit the title and theme, but lack the throwback energy of their newer material.

The 2022 album successfully shows Lupe’s evolution as a critical analyst from hip-hop’s margins The satirical “Stack That Cheese” on The Cool was funny and effectively made the point about the less than heady state of contemporary rap circa 2007. Drill Music in Zion is Lupe’s abstract way of grappling with the sub-genre that overtook his city and spread through the world – as well as the real life violence that has become inextricable from it. It’s not done in as overt a manner as Lupe’s previous hip-hop criticism, but the album does force listeners to grapple with their own relationship to drill.

When Pitchfork gave Lasers a 3.0 in 2011, it fundamentally impacted perceptions of Lupe with the kind of people whose opinions would have been fundamentally shifted by a Pitchfork review in 2011. Food & Liquor and The Cool had received near-universal critical acclaim. To the fans, it felt like the critics have decided it was time to tear Lupe down.

Foolishly, I took the Lasers hate to heart and essentially wrote Lupe off despite loving most of the album. Lupe had had an incredible five-year run, but the rap world was already shifting. It was ostensibly becoming dumbed down even more than what Lupe mocked early in his career. He was losing his place. Even before the release the album kept getting delayed, and Lupe’s relationship with Atlantic was disintegrating. The championship run was over.

Lupe Fiasco will go down in history as hip-hop’s Scottie Pippen. He’s one of the greatest of all time, but perhaps not the first name that pops into mind, Pippen played with Jordan, and Lupe broke through via Kanye and Jay-Z. Both were overshadowed by the GOAT-ier individuals whose Chicago teams they were on during their dynastic reigns. Look either up, and you’ll find people calling them “insane” for their eccentric worldviews. But you can’t dismiss their technical ability because their skills in their respective fields are undeniable.

Pippen played for 17 seasons. He won his last Title in 1998, his eleventh season. Lupe’s been in the music league for around the same amount of time as Pippen. And he’s still going. #33 cracked the all-time NBA stat lists in a few categories, but none of them at the top, and all of them peripheral or skill-based. He’s top 10 in playoff games played (#10), regular season steals (#7), and playoff steals (#2), and playoff personal fouls (#5). In my opinion, Lupe Fiasco is ranks near the top of many categories: multi-syllabic rhyming, high-concept thematic structure, longevity, artistic experimentation and creative evolution.

Lasers is like the Bulls’ 1994-1995 season. Jordan was mostly absent. They still made it to the Eastern Conference Semifinals, but the championship run was briefly over. “The Show Goes On” was a hit, but Lupe’s poppier turn and the album’s atypical production just felt flat. It didn’t feel right. He was experimenting with new forms, but it didn’t sound like the sound he actually wanted to pursue. Lupe eventually bounced back from Lasers, but at the time it seemed like he was finished.

I still think the Pitchfork rating was too low.

It’s rare that a debut is actually a true classic, even if it feels that way upon its release. Everyone who loved “Kick Push” hoped that Food & Liquor would be the next College Dropout. It came out a year after Lupe and his skateboard had hitched themselves to the back of Kanye’s rocketship. Craig Bauer, who also worked on Late Registration and Graduation, mixed the album. More so than at any point in Lupe’s career, contemporary audiences in 2006 were primed and eager for dense political and social lyricism over bombastic, horn-heavy beats.

Kanye had an atypical path to superstardom, but his success was then firmly associated with Roc-A-Fella, Def Jam, and the major label system. Lupe and his own 1st & 15th Entertainment was another example of independent hustle paying off with the majors, after he and his indie label signed a distribution deal with Atlantic. The deal followed a slew of other failed contracts, and no one knew the Atlantic deal would someday be deemed the same. The underground had been simmering for years beneath the surface, then exploded unexpectedly.

Lupe was like ‘Ye in approach and ethos, but he could really rap. He had more of an ear for melody and hitmaking than many of the other past and future protoYes (CyHi, Rhymefest, Consequence). So every skateboarding, backpack-wearing, Dave Chappelle’s Block Party-watching, Mos Def and Talib Kweli-worshipping mid-aughts hip-hop fan was eagerly awaiting for Lupe to usher the conscious underground further into the mainstream. Common had already transcended Chicago’s West Side for Hollywood and the mantle was Lupe’s for the taking.

Food & Liquor is smart and ambitious. The relatively profound exploration of the balance between good and evil was enough to make it feel like an instant classic. Back then, we had more of an attention span for a dramatic three-minute intro and a nine-minute shout-out outro. With the benefit of hindsight, the album isn’t quite there. It’s too sprawling and too disjointed.

The album’s biggest single was “Kick, Push,” which also happened to make Lupe a superstar. His main producer, Soundtrakk, was tapped into the sound of the times. The two of them made orchestral and huge music, but Lupe’s lyrics and flow were also a throwback. They were conscious like Common. He told third person stories like Slick Rick. Food & Liquor was the antithesis of the era’s flashy coke rap trends, while also reaching for an arena-sized sound.

The most dated parts of Food & Liquor are the songs that Soundtrakk didn’t produce. “I Gotcha” has a Pharrell beat that sounds like it had been previously passed on. Mike Shinoda produced “The Instrumental,” which sounds too much like a Linkin Park song (one area where Jay-Z’s input may have gone too far.) To be fair, “Daydreamin’” is one of Lupe’s best songs ever, but Soundtrakk actually didn’t produce it. Lupe apparently never made money off it either, due to label shenanigans and the cost of the sample.

Food & Liquor also presented Islam on record in a more straightforwardly religious way than the many preceding Five Percenter classics. Five years after 9/11, during peak Islamophobia, “American Terrorist” was much more of a political statement then than it would be now. It was clear from the start that Lupe was different and intriguing, and that he’d also have some views and qualities that would make it hard for the masses to accept him.

Some artists drop a refined, definitive statement album on their first attempt. When Food & Liquor came out, it would be reasonable to assume it was Lupe’s version. Thankfully, he had much more to offer and room to grow.

Released just a year after Food & Liquor, The Cool builds on the first album yet shifts into distinctly darker territory. The theme is more conceptual, but harder to follow. It has something to do with “The Cool” from Food & Liquor but with added characters called “The Game” and “The Streets” – I never knew about any of them until I looked this album up on Wikipedia despite listening hundreds of times. Lupe himself said, “It’s not a concept album; it’s more spread over like five [tracks], really abstractly.”

In my rankings, I tried to remain as objective as possible. Of course, objectivity is impossible. But I did try to remove the nostalgia factor from my listening of older albums. With The Cool, that moral code did not hold. It couldn’t. I simply wore this album out when it was released. I still love it now, perhaps only because I loved it then.

“Hip-hop Saved My Life” was exactly what teenage me needed to hear. “Go Go Gadget Flow” was just juvenile enough, too. I never really understood who Michael Young History was, but I definitely liked that guy. “Palaces” was a mission statement. “Cake” was catchy. “Dumb it Down” was genius. If the people wanted something stupid he could stoop low, albeit in the smartest way possible, like Kendrick on “Swimming Pools.” “No. 1 Headband” interpolated the old Kanye’s flow. “Bigfoot” predated Chance. For me, The Cool was aughts Chicago rap at its first peak.

I saw Lupe perform at Foellinger Auditorium in Champaign, IL. He was wearing a scarf. He said he was going to perform a new song and launched into “Superstar.” The crowd knew every word. Lupe was mad because the song hadn’t officially come out yet. But the explosive reaction confirmed what his lyrics said.

Damn, I really overlooked this album when it came out. It’s so good.

Drogas Wave has the most compelling narratives of Lupe’s discography. It’s also presented in the most straightforward manner. According to Lupe, the album is a speculative story set during the Atlantic slave trade, in which a group of slaves thrown off a boat discover that they can breathe underwater. Then they start sinking slave ships.

On other albums, Lupe would have used such a cinematic story idea as a starting point from which he’d explore related themes in an abstract fashion. On Drogas Wave, he sticks close to the plot. The spoken word interludes provide historical context. The production is bubbly and nautical. There’s a Caribbean, West Indies influence. It’s the best aquatic-themed hip-hop album from Chicago since Mick Jenkin’s The Waters.

Out of 24 tracks, however, only the first nine contain this specific storyline. From there, the allusions to the theme aren’t as overt. Depending on who you ask, what follows is either a brilliant commitment to the meaning behind the theme (because it shows Lupe embracing his freedom from Atlantic) – or its an aimless and overly long misstep that tarnishes an otherwise strong concept.

“Don’t Mess Up The Children” is another interlude that doesn’t directly relate to the history of the slave trade, but does talk about the importance of adults passing on the stories of ancestors and cultural values. The next song, “Jonylah Forever,” presents another alternate history. The song imagines what the life of Jonylah Watkins—a 6-month-old Chicagoan who was shot five times and killed while her father was changing her diaper—would have been like if she were allowed to live. Like most every LP in Lupe’s discography, you get the sense that this song is more closely related to the overarching themes of Drogas Wave than what appears on the surface. It’s never clear whether Lupe himself has worked out all the connections, but even the abstract threads holding his works together reveal more of a commitment to concept than most artists take. Drogas Wave has the best concept, so it’s one of his best albums even if that concept isn’t carried out the exact way it seems it might be for the first nine tracks.

There’s also a song called “Stack That Cheese,” which to someone who loved The Cool, is just catnip.

When the Great Beef of 2024 kicked off and corporate Times Square billboards declared “Hip-hop is a competitive sport,” many rappers jumped uninvited into the ring opportunistically seeking money or fame. Few were as qualified to enter the fray as Lupe Fiasco, who declared onstage at Coachella: “I will battle any motherfucking rapper, anywhere, any motherfucking time.”

Every no-name TikToker who two weeks prior would’ve sold a kidney for a Drake feature embarrassed themselves within minutes over “BBL Drizzy.” No one took Lupe’s bait. Other rappers ignored Lupe either because they no longer consider him relevant, because they’re afraid of how he systematically dismantled every shot that his estranged podcast host Royce Da 5’9” fired at him in their brief beef.

Watching the clip of Lupe fired up, screaming, and pacing amidst airhorns and cheers, you can tell that he means what he’s saying. Years ago, he shed the clout-seeking attributes that made him a star to hone and upgrade the technical skills that made him an MC. Cashing in on the resurgent battle rap trend monetarily would be a bonus. His tone and body language illustrate his desire to prove his continued lyrical excellence. “I don’t give a fuck how many records you sold,” he says, presumably to Drake. “I don’t give a fuck how many awards you have,” he says, seemingly to Kendrick. J. Cole had bowed out at this point, but J. Cole being mentioned in a Big 3 over Lupe is as preposterous as the concept of a Big 3 itself. Not worth addressing.

Rather than taking on an opponent, Lupe followed up on his threat with the release of a new album. Samurai’s loose concept is based on a scene in the 2015 documentary Amy, where Amy Winehouse leaves a voicemail for producer Salaam Remi comparing her lyrics to battle raps. Listening to Samurai without context, even Lupe’s MIT students would have difficulty identifying that thematic structure.

Intentionally or not, though, Samurai is structured in a way that feels like Lupe is battling everybody and anybody. Stripping it down to ten concise tracks and packaging it with Japanese artwork evokes Lupe at this later stage of his career: a well-trained warrior, so ready for challengers that none dare step to him. It’s like a less emotional, more controlled version of his Coachella rant: definitive proof that he can outrap anyone. Because the lyrics aren’t directed at another rapper in particular, and no one is there to confront his blade, it sounds like he’s battling himself.

Like every artist, Lupe is also embroiled in the eternal battle against time. To those who know Lupe from Food & Liquor and The Cool, it’s almost unbelievable that he’s still releasing new music. It’s nearly impossible that the music is this honed, this focused, this sharp.

In a Stereogum interview with Dash Lewis, Lupe mentioned that he recorded Samurai’s tracks before 2022’s Drill Music in Zion. That previous album, like Samurai and the rest of Lupe’s discography, also features an overarching and difficult to track concept. In some respects, it’s yet another version of Food & Liquor: the dark and the light, the struggle for good amidst the trappings of evil, and finding the balance in between.

Lupe is locked into quasi-battle rap mode, which somehow makes the music lighter, happier, and more enjoyable. Knowing that he recorded Samurai before Drill Music in Zion, it wouldn’t make sense to assert that Lupe’s mic skills have improved in two years. Both approaches serve the greater purpose of their respective projects. However, the timing of Samurai presents Lupe in his most polished form.

Lupe has been up. He’s been down. The one thing he’s never done is level off. Samurai is about as straightforward as it gets, which in and of itself is an artistic statement. He’s better like this, with the fluff stripped away. If you forgot about Lupe at any point in the past two decades, now is the time to tune back in.

I learned about Samurai when someone sent it to the group chat, saying, “2006 is back.” Then I read the venerable Paul Thompson’s 7.4 Pitchfork review. Anthony Fantano gave it an 8. It appeared as if our old Superstar had kick-pushed himself back into relevancy.

After critical fallout from 2011’s Lasers, Lupe spent a decade refining his craft in relative obscurity. His diehard fan base grew along with him, but the casual audiences who swayed their hands in the air to “Superstar” moved on. The value of “true lyricism” is ever-evolving, as is the collective assumption as to what “true lyricism” even means, but the flows and multi-syllabic rhyming structures Lupe has always utilized are now from a different era.

A short album with jazzy production, verbose lyricism and higher consciousness arrived at the ideal time. The West prevailed over Canada this season, but the Midwest is always engaged in the war for respect and appreciation from the rest of the map. Despite his age and veteran status, 2024 Lupe is among the best representatives of the region’s cultural achievements.

Two decades is a long time to do anything. If you’re good at something and love doing it, though, there’s no real reason to stop. It’s not shocking that aging athletes, politicians, and musicians linger too long in the denial phase.

You get older and music gets younger. Nonetheless, it rarely stops any musician from wanting to write and perform. It’s easy to learn about Samurai and think there’s no reason to listen to a Lupe Fiasco album – the same way teenagers who owned Illmatic on cassette might not be streaming the latest Nas album. But like Nas, Lupe has shown few signs that his age has diminished his artistry. Unlike Nas, his first album wasn’t a true classic. But as of now, at least to my ears, it appears that Samurai is.