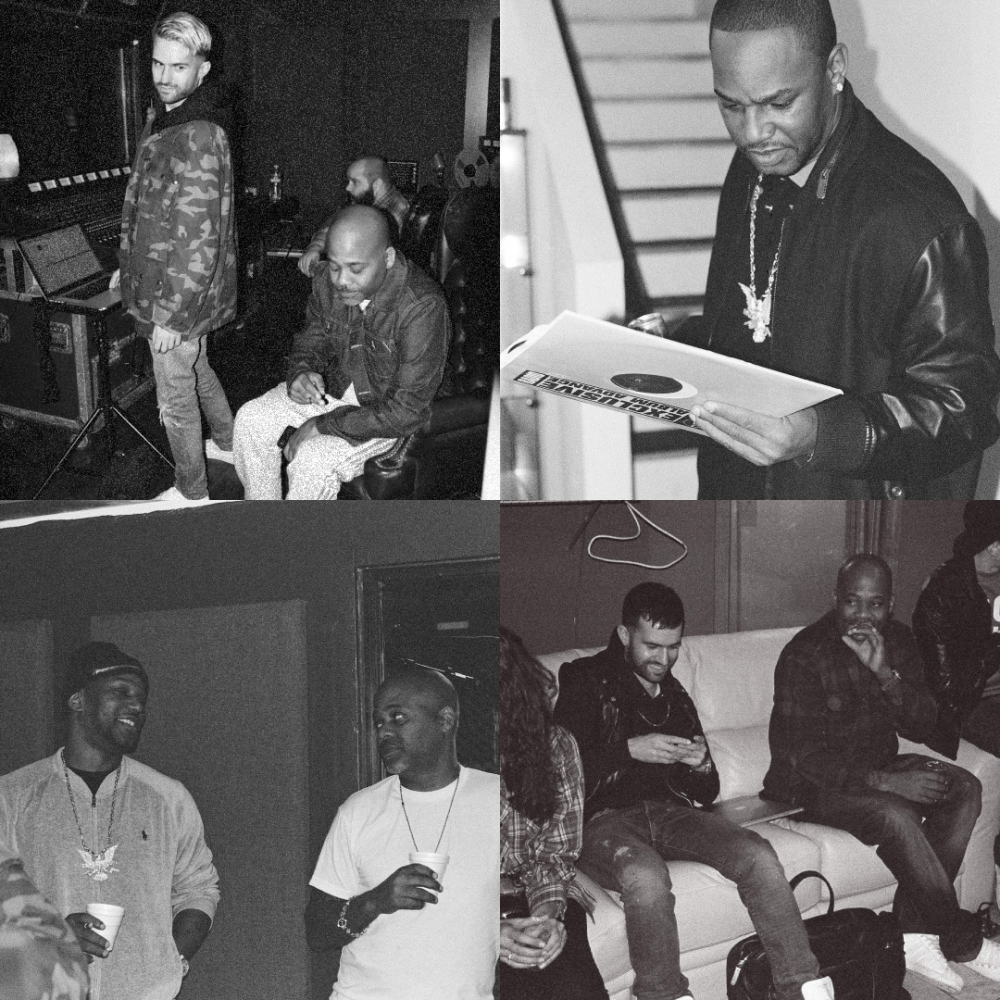

Image courtesy of A-Trak/Instagram

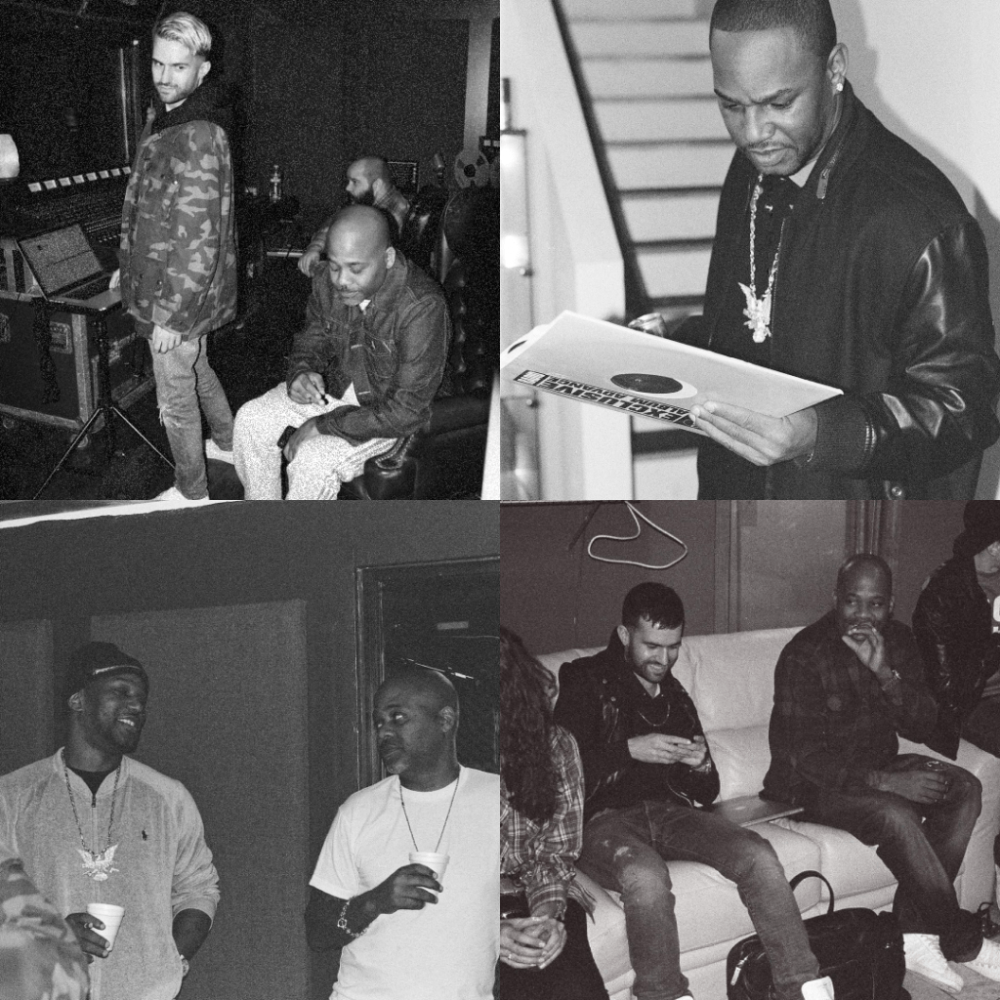

Image courtesy of A-Trak/Instagram

Patrick Johnson wants you to rejoice: it’s almost Pine Barrens season.

Damon Dash isn’t stressing about much at this point in his career – or if he is, he hides it well. As we talk over Zoom, he rolls up a joint while someone from his team stands just off screen, cell phone in hand to record his latest round of interviews for Cam’ron and A-Trak’s collaborative U Wasn’t There to repost on his Instagram Stories. These days, you’re more likely to scroll past Dame in the endless stream of the almighty algorithmic timeline than you are to see him promoting a new project – his frequent appearances in under-a-minute hustle culture videos find him dropping gems from what he’s learned in over three decades of a tumultuous career full of some major wins, but also plenty of personal loss. On this particular day though, he’s content and even surprised that this album, some eight years in the making, came out in the first place.

“Never let anxiety control your action,” he tells me between inhales. “The only thing that should give you anxiety is if it’s compromised your health and your freedom. And for me, maybe it’s a gift and a curse that I went through severe pain very early in my life. My mother died when I was 15 and then my girl died when I was in my twenties. And these are things most people go through when they’re older, but once you go through some real pain, [anxiety] does not bother you anymore. You get cool. That’s why I don’t want my kids to be too cool, ‘cause being too cool means you’ve survived a lot of pain.”

Being too cool has been a thriving business model for Dash and Cam’ron since the late ‘90s and early aughts when the Harlem rapper built a dynasty based on a singular iconography: an awe-inspiring vocabulary, nursery rhyme cadences and a winning strategy spearheaded by Dame’s foresight. For an all-too-brief moment in time, New York City belonged to Dipset. Throughout U Wasn’t There, Cam’ron is well aware of his place in hip-hop’s cultural canon, recapping his resume in the opening verse of “What You Do”: “On Fox 5, I cursed Bill O’Reilly out… Left my girl, I’m done with love and shit/ Went on 60 Minutes, told the world fuck a snitch/ Had the pink fur, pink phone/ Pink rings, pink chrome/ Produced movies with Queen Latifah/ Went to the Emmy’s smelling like Wiz Khalifa…”

Cam’ron’s momentum post Purple Haze, Killa Season and Crime Pays was supposed to move forward by veering left. Dash connected with A-Trak, another purveyor of the cool in his own right – through his Fool’s Gold record label, as a solo artist, a member of Duck Sauce, and a string of memorable Fool’s Gold Day Off concerts. Those free showcases melded hip-hop and electronic music in an effortless way that simply nobody else could have during that moment in time. While A-Trak initially reached out for a lone Cam’ron feature, Dame had something more expansive in mind. “I liked what he was doing [with Fool’s Gold Records] you know – I’m into that indie, DIY, cool kid kind of thing. And he had that kind of lifestyle, pause, movement,” Dame revealed. “At the time, I don’t think Cam really had an understanding of how the rest of the world looked at him. What I learned was that the indie white kids were obsessed with Cam’ron back in the day… so I knew that would be a good project for that crowd and that would also bring Cam’ron into the festival world.”

Federal Reserve was announced in January 2014 through a cover story with Complex and a string of singles like the Juelz Santana-featuring “Dipshits” and “Humphrey” (which can now only be found in the archives of Dailymotion, glorious airbrushed artwork by Kunle Martins of the irak crew still intact). Then… years of radio silence. See the double-edged sword of being too cool also means, in Cam’ron’s case, convincing him to give a fuck. You can refer to Dipset’s VERZUZ appearance for a somewhat recent example.

“Working with Cam is like lightning in a bottle. So being able to get ’em someplace at a time and capture that to get everything we need, that in itself was an art,” Dame revealed. “If you don’t know how to talk to him, things can go bad quickly. And I remember A-Trak does not take no for an answer and that’s why I like him. He’s a little tough motherf*cker and he stands behind what he believes in. You’re not gonna push him over. And if he wants something done, he’s aggressive about it.” As A-Trak tells it: “We both got busy. Cam went on tour, I went on tour. Cam kind of just works when he feels like it, which at this point in life as he should, you know? But there’s a point where we kind of lost his interest.”

A-Trak was a turntable prodigy before he hit puberty. The Montréaler entered Dame’s sphere when he was around 15 years old but by the time they reconnected, A-Trak had taken center stage during the massive EDM explosion of the 2010s where he “was mostly producing house music, but hip-hop is always my first love, my first passion.” The chance to work with Cam’ron and Dame was a full-circle moment. “Back up in Montreal, my brother [Dave 1] was managing a record shop… He would order vinyl and Cam’s first album, Confessions of Fire, stayed on those racks for quite a while. Sadly, Montreal was not really buying that LP… My brother moved to New York ‘cause he went to Columbia and I would come down and just rock out to those [Dipset] tapes in those years. Fast forward 15 years later and I’m making a record with the head of that crew. We were transported back to those years when we were just fanning out the first time around.”

Even with both feet firmly cemented in the booming electronic landscape, A-Trak remained a bonafide hip-hop historian with an encyclopedic knowledge of all things Dipset. With U Wasn’t There, he aimed to curate a project where all of the different eras and soundscapes of Cam’ron’s career – from his collaborations with Heatmakerz, Dame Grease, Just Blaze – were properly paid homage to without sounding like a greatest hits compilation. “There is such an aesthetic to Dipset,” he detailed. “I just tried to obviously not replicate it ‘cause I’m not trying to only make a retro album. You know, understanding the lines within which we color and then make my version of that.”

But as the years passed, the context and sound of the record had to change. Collaborative projects between a lone producer and rapper had become common-place. Engineering had come a long way – mixes became cleaner, juxtaposing Dipset’s collective rough-around-the-edges quality. Cam’ron’s discography grew and matured while his back catalog aged like fine wine. “Whether it be the concept of producer-rapper collaboration tapes or even just sample based hip-hop, there’s a lot more context for this kind of record now than three to four years ago, let alone seven or eight years ago,” A-Trak told me. So he recruited a cohesive collective of co-producers throughout to help him capture the magic. The intro “This Is My City – Federal Reserve Version” taps Thelonious Martin for a chipmunk soul, gospel choir anthem but with a modern touch of booming bass and hi-hats. While Cam’s verse first appeared on a Purple Haze 2 cut, the original instrumentation elevates the song to a different level as the beat cuts out for “love my hood, but to make it out… wooh, what a feeling!”

On “What You Do,” !llmind and A-Trak set the pace with upbeat piano keys and triumphant horns. DJ Khalil reimagines a reggae turn on “Think Boy” and again with co-producer Simahlak for “Dipset Acrylics.” A-Trak’s signature scratches add depth to DJ Thoro and G Koop’s “Cheers” while Cam’ron shows up nostalgic and most importantly: motivated. 2000s era keys recall the perfect summer day on the block – Cam adds in ad libs of snorting cocaine in a way only he can while painting a vivid picture of “eating sorbet in Bermuda.” “The fact that it took this long really worked out because the final version of the track, with what I was able to put back in, was key,” A-Trak said. “I think “Cheers” has some of the top two Cam verses on the project. You gotta put “Cheers” in there. Probably like top two, top three verses of his. He gets into “computer’s ‘putin’” territory. I think when Cam raps “I like the picture, ‘cause I like the picture” is [super] memorable.

U Wasn’t There was never on schedule, but it arrived at the perfect time. The result is a rare one: a free-flowing tape that’s unassuming but essential Cam’ron. At just under 30 minutes, it should leave you wanting more. Cam’ron is reflective, revealing, absurdist and hilarious all at once, backed by the perfect soundscape from the people who know him best. Three icons in their own respects got back together to make good on a near-decade-long promise when nobody was holding them to it after all of these years. When I asked about whether Cam’ron had reached out about the new project post-release, Dame laughed and said, “No, but he did send me the black emoji fist over DM the other day.”

Cam’ron wasn’t available for comment. These interviews were conducted separately and have been condensed and edited for clarity.

There’s a lot of nostalgia around this project without being overly revisionist. You had a heartfelt Instagram post where you wrote, “at this point in my life I want to build monuments for the shit I care about.” You were able to do that some eight years after Federal Reserve was originally announced. How’d you get to this point with U Wasn’t There?

A-Trak: I feel like that realization for me probably came in the second half of the last decade of the 2010s where, if you look at sort of what happened to the DJ scene at the beginning of the 2010s, there was the massive EDM explosion. Which was big business for everyone. For a long time I’ve had one foot in hip-hop, one foot in electronic music when that stuff took off.

The electronic side of what I do just went to a massive scale. But it was kind of a whirlwind for a lot of DJs where things moved really, really fast. The whole landscape was changing. Every year there were Vegas residencies, there were endorsements, there were magazine covers and all kinds of stuff, which seems great. But I think it was also a little disorientating for some DJs.. There was this sort of background pressure for a lot of DJs to follow a path that was defining itself during those years – now DJs make songs for Top 40 radio.

And when that bubble burst in the mid 2010s, I looked at it on some like – I’m just gonna continue doing what I’ve always done and you know what, that’s probably what’s best for me – to just double down on the things that make me me. So at that point in time, I had already started the Cam’ron collaboration, ‘cause that started in 2014. Duck Sauce had already blown up. Fool’s Gold was close to 10 years old already. Even turntablism itself was kind of at a place to adapt to the technology for the first time in a long time. There were new mixers coming out with a whole bunch of new functionalities that was like literally inspiring me to come up with new DJ tricks in a way that I hadn’t been inspired in a while.

All those things combined as this sort of tornado passed and a lot of my peers were left scratching their heads and maybe soul searching a bit. And I think that also led to a thought process of – I’m lucky to be in a position where, at that point in time my career was hitting the 20 year mark. I still love what I do. I get to play what I want at shows. I don’t have to deal with requests. I sign music that I am passionate about on Fool’s Gold, and I get to work with my friends. And that’s a luxury. That’s amazing. In a sense, I get to decide what I’m gonna devote my time and energy on.

So if I’m gonna choose what I’m gonna put my time and energy into, well, I also have a clear sense of what I’m passionate about. Certain artists that really shaped my palette, my taste, my career, and people that I actually enjoy working with. And if I’m lucky enough to be in a position to choose who I work with and to define how I project my identity in a sense, right? Like if I’m putting scratch videos on my Instagram, if I’m doing a passion project on the SP-1200, that’s just me doubling down on what gets me geeked and what I’m excited about.

And the idea of building monuments for certain movements in the artists and sounds that I’m passionate about, that fits into that lens too. And that fits into that phase of my career of like, alright, DJing’s gone through a whole shift of changes compared to the Stretch and Bobbito era, the era that I come from. And now we can all define what we want to do. Well part of what I love is to pay homage and use my voice, and use my platform, and use even my sort of curator sense to do something like this Cam’ron album where as a fan, I want this album to exist. I wanna have that project to listen to even myself. So I’m just gonna tough it out for forever [laughs]. For however many years it takes to get it to the finish line and stay passionate about every single detail until the last second, into going into the artwork and the marketing and everything. ‘Cause I care about this.

It’s been a trip for me. As this record actually came out, to think not simply how many years we’ve worked on it, but look at what happened to the landscape during those years. It’s changed a lot. It’s interesting how through all the different shapes and forms that the music landscape has taken during those years, as much on the hip-hop side, as on the general DJing side and everything else, there’s a place for a record like this.

Hip-hop is also flooded with collab tapes now, which really wasn’t as common back when you, Cam’ron and Dame started working on Federal Reserve. I’m interested to hear your thoughts on where this fits into the present landscape after working on it for eight years.

A-Trak: When we decided to pull the trigger on releasing the album this year, I got everything mixed again because of how much the hip-hop landscape has changed since the last time that we had a release date for this record. So whether it be, like you mentioned, the concept of producer and rapper collaboration tapes, or even just sample-based hip-hop – there’s a lot more context for this kind of record now than three, four years ago, let alone seven or eight years ago. I definitely have this, ‘never on schedule, but always on time’ feeling about this album where it did come out in a time and place where there’s context for it.

When we started working together, it was just Dame’s vision in a sense. Zooming back to 2014 for a sec – Fool’s Gold Day Off was probably at the biggest scale that it ever reached. The original Rock the Bells was no more, Rolling Loud didn’t exist yet. Even though Fool’s Gold Day Off was always a boutique festival, at the end of the day, we were kind of the only name in town for putting rappers on a festival stage during that time period. And funnily enough, I put AraabMuzik on the festival stage and I was the first to do that. He was managed by Dukedagod who worked with Dipset. After I put AraabMuzik music on Fool’s Gold Day Off, he got a booking agent and next thing you know, he was playing legit festivals in front of 10,000 people. So a lot of rappers were still playing walkthrough performances at clubs – You know the ones with the funny flyers with like some random girl on a flyer and the rapper’s name. And the rapper’s in VIP with a mic doing shoutouts for three songs then picks up a bag of cash.

That was the standard for a hip-hop performance at that point in time. At Fool’s Gold, we’re putting on real shows. Dame was aware of that but I didn’t even realize how aware he was. I’ve known Dame on and off over the years. He was there when I met Kanye way back in the day. I was working on a couple of records just for fun and I thought it would be cool to get a verse from Cam’ron. So I just called Dame to see if I could get a verse from Cam not even sure what their status was, if they were even working together closely at that point in time.

And Dame immediately had this bigger vision where he was like, “Yo, you’ve been doing those Fool’s Gold shows. I saw what you did with AraabMuzik music. Cam should be with that. You guys should do a project. Cam just needs to meet you and you gotta build trust with him. So I’ll connect you guys, I’ll be there the whole time. As long as he gels with you, you guys should just do an EP and then tour it. You put it at your festival.” All of that just off of a phone call with Dame where I was only like, “Hey, can I get a verse?” That’s how the collaboration started. We recorded a couple of songs, announced Federal Reserve, didn’t finish the project, and ever since that point there’s been this sort of demand or anticipation for it.

So what happened?

A-Trak: We both got busy. Cam went on tour, I went on tour. Cam kind of just works when he feels like it, which at this point in life as he should, you know? But there’s a point where we kind of lost his interest. And as he went on tour the next thing you know, I think two years went by and then we got back together two, three years later, Dame kind of got the itch again and rallied both of us up. We had something ready to cut and put out by 2018 and we wanted to sign it on neutral ground ‘cause all of us have our own labels. So we signed to Empire and we were about to put it out around early 2019.

I had mixed the whole album myself, I remember really spending a lot of time thinking about the sound of those beats, how at that point in time mixed sounds had gotten really polished and clean – just engineering in general had come a long way. But that wasn’t the sound that I wanted for Cam’ron. When I would listen to those classic Heatmakerz beats from the Diplomatic Immunity era, there was a slight distortion and this rough-around-the-edges quality that I wanted to keep. You could tell that The Diplomats were putting out tracks that a lot of times weren’t even professionally mixed. They would just get a beat from the producer. record to it, then drop it – not even get the stems or even get it mixed. But there’s something about that roughness that was part of the character of The Diplomats that we all liked.

On some engineering shit, at that point in time when I was finishing the mixes before the pandemic, there wasn’t much current context or even current projects to compare the sped up soul beats with hard east coast drums to. I was just literally referencing 2003 beats, Dame Grease and producers like that. The whole rapper and producer album was starting to happen a bit. I don’t remember exactly the timeline, but the stuff that Freddie Gibbs and Madlib were doing, and then Freddie and Alchemist, things like that were starting to pick up some steam. Going back a couple years prior, of course there was 9 Wonder and Murs – it’s not a new concept, but that became such a thing in the last couple years with what Muggs did and what Alchemist did, of course, the whole Griselda thing.

I think looking at the last couple years as far as sample-based music between what Griselda did, what Alchemist has been doing, Mach-Hommy, and of course Roc Marciano, who I think is the godfather of this whole resurgence of haunting loops, there’s now a lot to compare [U Wasn’t There] to. Now this wasn’t a ‘no drums’ album in the way that the sort of Roc Marci influence and then the Griselda sound became – of course there were hard drums on this, but now there was just more to compare this to. I ended up getting Eddie Sancho to do new mixes on the whole album this year. Then we put it out. I had time to think about this project for many, many years and you know, everything is based on context.

Dame Dash: A-Trak fought for it. Every time we would start, we couldn’t finally just get it out. We didn’t roll it out with videos and we have a lot of assets to promote it, but it’s just, you gotta get Cam when you can get him. So he finally approved it, I guess. And A-Trak had the deals all set up and honestly, this is the way I like to do music where I don’t have to be the administrator. I like to curate and be a part of the chemistry of the art and bring people together. I don’t like to deal with the business ‘cause people get on my nerves. A-Trak and his crew did all the shit I hate to do and now we could just sit back and see what it do, in a very organic way, which is always cooler anyway. Sometimes no strategy is the best strategy.

It is kind of strange that people now talk about marketing and album rollouts as an extension of the artform.

Dame Dash: I don’t fuck with the industry. Like, if someone has an industry, it’s only gonna behoove the people that created it, not the people that make money working for it or get exploited. So you have to make your own industry and you have to make your own protocol for the way you monetize your stuff. So if you put your destiny in the control of another industry, then you’re saying, you guys make money off it first and then I get what’s left. That doesn’t behoove me. The only way is to stay creative, to stay inspired and to stay making cool shit. As long as you’re inspired by culture and you continue to create… You get so sick of working with the industry that you quit the art. I never quit the art, I quit the industry… I am artist first – always have been, which is why I don’t do shit for money. I do shit for art, which is why I’m the worst businessman, but I’m the best artist.

Dame, I want to get your take. What was it about A-Trak that made you want to scrap the initial idea of a quick feature and instead want to work on a full EP with Cam’ron?

Dame Dash: Well, I was in London with A-Trak when he was like 15 and I tried to put him with Samantha Ronson and I just happened to have Kanye with me and he was like, “Nah, I think I’ll go work with Kanye.” I was like, either way, it’s Roc-A-Fella, I don’t care. So I always kind of knew him. And then I liked what he was doing [with Fool’s Gold Records] you know – I’m into that indie, DIY, cool kid kind of thing. And he had that kind of lifestyle, pause, movement. So when he called me, I was always looking at what he was doing as cool regardless – the festivals and the artists that he aligns himself with and he does the rock and the house. Everything he does, it’s a good collaborative, cool thing.

So when he called, I was like, “Nah, fuck a single, let’s do a project.” At the time, I don’t think Cam really had an understanding for a long time of how the rest of the world looked at him. When I was doing DD172, what I learned was the indie white kids were obsessed with Cam’ron back in the day. I would do things like take him or Jim Jones to places where they would never go – some place in Brooklyn in a warehouse and have them perform and they would just – it was ridiculous. So I knew that would be a good project for that crowd and that would also bring Cam’ron into the festival crowd. The way Dipset used to do their shows, I always knew it wasn’t sustainable.

It would be like, yo, you can’t have a hundred people on the stage and you’re performing over a track. That’s not festival shit. So I never saw Cam really get the benefit of doing festivals like the rockstar that I had viewed him to be. And I thought that that project would also get him into the festivals as well. Above him being a hip-hop legend, I always looked at him as almost a rockstar, an international sort of a personality that the rest of the world, other than outside of hip-hop… I never thought he hit that peak. And I never give up. So I just felt like this is that one more shot to get Cam where I want him to go. I don’t want Cam to be an artist that’s only performing “Oh Boy” 20 years later. He’s an artist that should be performing current records.

Working with Cam can be challenging because he’s a true artist that doesn’t do too much for money. He does things for whatever makes him feel good, which can inconvenience everyone that he’s working with. So working with Cam is like lightning in a bottle… being able to get ’em someplace at a time, capture and get everything we need, that in itself was an art. It’s hard sometimes to schedule greatness… And I remember A-Trak does not take no for an answer and that’s why I like him. He’s a little tough motherfucker and he stands behind what he believes in. You’re not gonna push him over. If he wants something done, he’s aggressive about it.

U Wasn’t There is a testament to not just you and Cam’s decades of being relevant, but also the fact that you’re still paying attention to where hip-hop is presently to make this project right at home in 2022 in a way that could have been different in 2019 or even 2014…

A-Trak: It’s like a sculpture man – you have your sculpture that’s practically done for a long time where you’re looking at it and you’re like, “I can’t quite tell what it’s missing, but it’s almost there. Let me walk away from it for a second, come back to it.” And when you come back then you’re like, “Oh no, I know it needs to have this different kind of sheen actually, or the edges need to be rounded off differently.” You need to put little touches on it, and a lot of what I did over the last couple of years was just coming back to it with clarity and the current context to be like, “Oh no, no, no, we need to actually take this form.” Truthfully, the last iteration of the project before the pandemic that almost came out, there was a point in time where a couple songs got removed from the record and then this year when we got back on the same page and decided to put the record out, I was able to put most of it back together.

The whole Federal Reserve project was always meant to be an EP. It just so happens that we recorded this amount of material over time and when I was able to tally everything up this year once and for all, did the new mixes and kind of looked at everything, it was nine songs – we didn’t even necessarily set up to make an album. But the more it came together, especially once we started having Dame’s skits, I got into album mode in the wrap-up period.

The instrumental curation, the sequencing, the skits – it’s clear that you’re not only a fan but an expert of the different eras of Dipset and Cam’ron lore. Do you remember the first time you heard a Cam verse?

A-Trak: Man, the first time I heard Cam was probably 357, which I think came out of ‘97, which is a trip ‘cause our careers have had the same timeline. My career took off when I won the DMC battle in ‘97. It’s just that he operated on the major label scale early on, whereas I kind of of slowly built my career up. I remember going to New York with my brother [Dave 1] around those years and just buying mixtapes from the bootleggers. There was a point where once Cam’ron was hot and he was on those freestyles, he was doing joints with DMX and on the same timeframe as when The Lox were blowing up. Cam was doing the fast flow, like right before “Horse & Carriage” and I remember really just really being into him and the style beats that he had.

I believe Dame Grease was doing at least some of those beats, where it was kind of the Jiggy era, but the shit that Cam and DMX were rapping on still had sampled drums and these little chopped up stabs, so it still had grit. It wasn’t full [Korg] Triton, which I had a little bit of a hard time with the Triton sound in the beginning. I was really a purist, which, you know, I was wrong, but at that point in time I needed some sort of grit in the beats that I was hearing. And I liked that the beats that Cam rapped on had that. But his flows were crazy impressive. Obviously he slowed down afterwards, but I was a fan right from then.

At that point in time back up in Montreal, my brother was managing a record shop. It was one of the few hip-hop record stores in the city and he was the buyer also. So he would order vinyl and Cam’s first album, Confessions of Fire stayed on those racks for quite a while. Sadly, Montreal was not really buying that LP. So his record cover is a record I saw for a long time on that wall. No disrespect of course. I was familiar right from the start and stayed a fan of the many evolutions of Cam’ron. On S.D.E. he had “Losin’ Weight” which was crazy and I was a huge Prodigy fan.

In 2002, 2003, Cam emerged with The Diplomat sound that we now know – kind of slows down the flow, gets a little more absurd with the lyrics. The persona takes shape as The Diplomats are putting out mixtapes. It was 2005 or so when I really wanted to make a song with them but I couldn’t even get to Cam in those years. But a friend of mine, through a connection with Roc Raida, rest in peace, who was one of my mentors as a battle DJ, connected me with a dude who helped me get JR Writer, Hell Rell and 40 Cal on a song. So I made a song with them, who were sort of like the junior team of The Diplomats called “Don’t Fool With the Dips.” So I’ve been trying to work with these guys for a long time [laughs].

This project almost didn’t see the light of day, so what about Cam’ron kept you coming back for nearly a decade to get U Wasn’t There across the finish line?

Dame Dash: It was like capturing friendship and capturing fun, which is the way art should be. For me, when someone just has subject matter and they write about it and they’re strategic, that’s not art. That’s more business. But when you create a vibe and just catch whatever comes from it, that’s art. But you have to capture the essence of it. And that’s every single thing creatively that I try to do. I don’t try to monetize anything contrived. What I try to do is capture authentic moments and put ’em in different vibrations.

The interaction between Cam’ron and A-Trak is interesting because A-Trak’s always trying to find a way to communicate with Cam’ron without offending him and that used to have me cracking up. I think we all had our different moments that triggered enjoyment, pause, from the whole [time]. But at the end of the day, just hanging out and having fun in environments where it was just us without the bullshit of other people’s energy.

A-Trak: As far as why I’d wanna work with him, I was just always a fan. He’s one of my favorites – his verse on “The Roc” with Memphis Bleek and Beanie Sigel is one of my favorite verses by anyone ever. I was always more than down to work with him period. And especially by the time we started Fool’s Gold and by the time I was shaping my place in the New York landscape and in New York culture, he had emerged as this Tumblr-era iconic figure too. I moved to New York, I was passionate about New York, things that were part of the New York iconography were important to me. And Cam was just one of those ultimate figures. You put ’em up there with Ghostface and in the light where it’s just these truly one of one artists whose lyrics are practically on some Dada levels.

Once we started working together, it was interesting to observe him too ‘cause clearly this is someone who has been rapping since he was a teenager and who does this in his sleep. He has a studio at his crib in Jersey. So that first summer that we were recording together, it would basically be me and Dame linking up with Cam and going to his crib in Jersey. He’s got an engineer at the house and we would just record on his setup. He doesn’t do a hell of a lot of takes. He writes the verse pretty fast, does the first take. And if there’s a couple words that don’t come out just right, he’s gonna layer it with a bunch of ad libs and backups anyways, so they get fixed in the stacks. It comes together pretty fast. He’s not the type of artist that I saw, at least with me, who will really second guess something once it’s recorded or come back to a song and be like, “Oh, well maybe we should change this verse or that hook.” It was more about capturing a moment in time. I would play him beats and if he fucked with something, he would write to it and record to it.

I think a lot of [the songs] were also the product of what was going on in the room. And the thing is, Cam and Dame hadn’t spent as much time together in the years prior to that. They each had their respective careers and they each had become legitimate businessmen. Cam’ron, outside of rapping, is an excellent businessman. He knows how to read his contracts too – he’s really on top of his shit. So it felt like getting to the rap was almost like bringing him back to the thing that he does in his sleep.

Cam and Dame would be catching up and I would sort of be the fly on the wall for that. I think that having a sort of innocence in the room and having a lot of reminiscing and a lot of just cracking jokes between people who have been cracking jokes at each other since they were teenagers laid a certain tone for a lot of the recording sessions. I was realizing that part of my role as a producer too is not only to make the beats or choose the beats or rework the beats, but also to be mindful of the actual vibe of the room as well – to make sure that everybody’s in the best mindset to be recording.

Dame helped a lot in that respect too. By that point in time I was mostly producing house music, but hip-hop is always my first love, my first passion. So I’m always excited to make music, but I wasn’t exactly sitting on 50 beats myself. But I have a bunch of friends who are great producers. To me, a beat for Cam’ron and Dipset needs to be produced in a certain way. So I would be looking for rough beats that people around me had started where I would hear something in the sample or in the sort of cadence of the drums. A lot of times I was looking for samples that felt like I could bring it to a Dipset place.

Once I had stems and I would record Cam over that rough beat, then I would rework the beat, especially the drums and basslines to give it that sort of the feeling that I was describing when I was listening to a lot of Heatmakerz, Dame Grease, Just Blaze.

Then there was another step of getting samples replayed, working with the people doing the replays and a lot of times we would replay them in a different way so that it’s no longer a clearance issue. That sometimes brought the beats to a whole new place. A track like “Think Boy” was an entirely different beat when it first started. And then I recorded the vocals, basically remixed it, put a whole other beat to it, and there was still a sample in it so I removed that sample entirely. So by the end there was nothing in common between the original beat, the new beat, but it’s the process of imagining a beat that those flows would sit well on. And that would also kind of tick a box in the album that I’m trying to shape. I was always a fan of reggae beat Cam’ron, ever since “What Means The World To You.” “Dipset Acrylics” ticked that box but “Think Boy” was a new composition with DJ Khalil and some of his musicians where I chose to bring it in that direction.

Was there anything that A-Trak or Cam’ron did creatively that surprised you on this record after working with them for so long?

Dame Dash: Yeah, there were a couple of records that I was like, damn Cam can still really rap. To me, Cam is almost a bit different than he was before. I guess it’s more evolved. Back then, it was evolved but he still had the recklessness of when he was young. So it was like an evolved version with the recklessness still, like a glimpse of the old Cam but with almost better rap skills. I always loved that A-Trak has a pure understanding of the Dipset sensibility of the beat and the essence of it. He knew what beats to bring and he knew the direction of the records he wanted. No one was trying to make a pop record or a hit record. We were just trying to make authentic, real records. I liked that he was fighting for that and that’s why I fuck with him, pause. That part almost wasn’t surprising.

It was just sometimes when you suspect something and then you see it. I suspected A-Trak don’t take no shit, but he really don’t – I saw it. He stood up to me and Cam several times, he’s not a pushover. To actually see it’s still a little surprising – I still grin when he’s fighting back with me, you know what I’m saying? He never goes backwards, but when he feels something, he stands behind it no matter what. So I like all that.

Between reggae beat Cam’ron, reflective ‘respect my resume’ Cam, and some Easter Eggs on the different eras of what could’ve ultimately been Federal Reserve, there’s something for everyone. What made you kick this project off by revisiting Purple Haze 2’s “This My City” with a chipmunk soul and gospel flip?

A-Trak: It wasn’t remade – that version was done first. That was originally a beat from Thelonious Martin that I played for Cam. The verse had already been written and you could tell he thought, “Oh, this is a beat I can do this verse on.” We recorded it then I went and did my thing to it, took out the drums, put in new drums, reworked the sample, all that kind of stuff. Somewhere along the way Cam was working on Purple Haze 2 and he put that verse on it. I was like, damn, that was my album opener. Time passed and you know, it was no longer a question of having to choose one or the other. That was one of the benefits of having a little bit of time pass where we could still use it.

There were a couple of last minute switches. Even as the album was delivered, to be honest, “Ghetto Prophets” was gonna be the lead single and we had a different hook. We had to switch it, switch the guests kind of at the last minute. There were a couple of issues with clearances, so as we were getting ready to drop “Ghetto Prophets” as tentatively the first single, we realized that we didn’t have a hook on that song anymore. We were able to get Conway literally at the last second, but in the meantime we had to go to Plan B for a lead single and that’s where “All I Really Wanted” came in.So some of that was just bob and weaving through the last couple of obstacles of getting this album ready to release in the last month.

Up until literally a week before release, we had to switch a vocal on another song, too. As much as this record’s been in the vault for a while there were twists and turns until the very last second [laughs]. But once we got to the conversation of choosing “All I Really Wanted” as a first single, it was a, “Oh wait, that makes perfect sense” moment. It shows Cam’ron in this reflective place that he’s in on this album, which feels different from his other projects. I even have scratches at the end. It shows the collaboration between him and I. So it actually felt like a perfect choice and I’m really glad that we led with that.

We’ve talked a lot about context with this album release, this whole concept of timelessness – never late, but always on time. And we get to see Cam’ron at his most reflective yet, looking back on a 30 year career in hip-hop with these iconic moments: O’Reilly Factor, pink fur, Anderson Cooper. How much did Cam’s present influence your decisions on the project?

A-Trak: You know, I’m not in his head, so I don’t even know exactly what Cam was thinking about. And now that I think about it, “What You Do” was also a beat that I switched afterwards where I literally remixed it with the help of !llmind and some of his co-producers. But when we first recorded it, I just remember that he heard a beat and had an idea right away. Cam didn’t even make a big fuss about it.

I do think the fact that Dame was there with us when we made these records, they were reflecting on their lives a lot in general ‘cause they were reconnecting. There were a couple of other people there, so they were commanding the room and making everybody else laugh by telling stories in between recording songs. Man, they were just laughing and reminiscing and I really feel that it seeped its way into some of Cam’s writing.

I was surprised that he asked me to pitch down a vocal cause you know, you don’t really hear Cam’ron all over screwed up vocals. So he laid down “What You Do” and the way he wove his lines around it – we were just cracking up. It was recorded pretty fast. It seemed like the easiest thing for him and clearly he’s aware of his own iconography.

What was it like sequencing this eight year odyssey with your brother, Dave 1?

A-Trak: He and I are co-executive producers on this project, and we’re both longtime Cam’ron fans. So we would think about, well, okay, is there a style of Cam’ron or Dipset beat that we don’t have that would be good on this project? I mentioned “What Means The World To You” earlier, but even The Heatmakerz were sampling reggae too – “Dipset Anthem” is a reggae sample. To me it was one of the things that always worked well with Dipset beats that I wanted to try.

It was that simple – it’s just nerding out over production styles. It gets even more nerdy than that, literally down to the choice of every snare, down to the styles of hi-hats and quantizing styles. There is such an aesthetic to Dipset. I obviously tried to not replicate it ‘cause I’m not trying to only make a retro album, and I’m not trying to out-Heatmakerz The Heatmakerz or out-Just Blaze Just Blaze. But we understood the lines within which we color and then made our version of that, and I like that exercise.

I don’t think [Dave 1] and I disagreed on anything with this record. He would help me keep track of the big picture and if I was in the weeds of recording with Cam until 3:00 AM and just trying to come home with files that I knew I could fix up later… he and I would share a folder and just listen and he’d be like, “Yo, he killed it on this one. You’re gonna need to rework that beat a little bit, but you have what you need.” But then he would also be like, “Man, if only you could get this kind of song…” We would workshop the ideas and then the next time that I was in with Cam, I would try to steer it in some sort of direction and then I would come home with files and rework.

It took both of us back to fan mode and listener mode. Dave had just moved to New York in like 2002 or so, before I did ‘cause he went to Columbia, and so he was there when Dipset tapes were coming out and I would come down and visit him and we would just rock out to those tapes in those years. So fast forward 15 years later and I’m making a record with the head of that crew. We were transported back to those years when we were jamming to those records the first time around

Dame, did you ever think that in 2022 that you and Cam would still have a foothold in the culture, even with how young and how ever-changing hip-hop is? That you’d be able to release a record like this and still get a response?

Dame Dash: If you take this shit too seriously then you’ll always be like… anxiety. But I guess if it was what was paying my bills, I might approach it differently. But that’s what’s so genuine about it is it’s more like, this is icing on the cake. We already did all the business, now let’s just do shit. This project was pure fun for me, purely so I could get back on the stage with Cam so we could still fuck around, pause.

I’m not in the music business anymore but I have enough legendary friends, brothers that whenever I get inspired, ‘cause I keep a studio, I keep a live band, I have the ability to capture a moment, a freestyle, anything… because the coolest shit is never contrived… Music after a very short time for me became something ancillary. It became a vertical to everything else that I was doing. So would I be able to just put a record out this old and it still be hard to the young kids? Pause. Nah, I am surprised. I’m actually really happy about that.

The electronic side of what I do just went to a massive scale. But it was kind of a whirlwind for a lot of DJs where things moved really, really fast. The whole landscape was changing. Every year there were Vegas residencies, there were endorsements, there were magazine covers and all kinds of stuff, which seems great. But I think it was also a little disorientating for some DJs.. There was this sort of background pressure for a lot of DJs to follow a path that was defining itself during those years – now DJs make songs for Top 40 radio.

And when that bubble burst in the mid 2010s, I looked at it on some like – I’m just gonna continue doing what I’ve always done and you know what, that’s probably what’s best for me – to just double down on the things that make me me. So at that point in time, I had already started the Cam’ron collaboration, ‘cause that started in 2014. Duck Sauce had already blown up. Fool’s Gold was close to 10 years old already. Even turntablism itself was kind of at a place to adapt to the technology for the first time in a long time. There were new mixers coming out with a whole bunch of new functionalities that was like literally inspiring me to come up with new DJ tricks in a way that I hadn’t been inspired in a while.

All those things combined as this sort of tornado passed and a lot of my peers were left scratching their heads and maybe soul searching a bit. And I think that also led to a thought process of – I’m lucky to be in a position where, at that point in time my career was hitting the 20 year mark. I still love what I do. I get to play what I want at shows. I don’t have to deal with requests. I sign music that I am passionate about on Fool’s Gold, and I get to work with my friends. And that’s a luxury. That’s amazing. In a sense, I get to decide what I’m gonna devote my time and energy on.

So if I’m gonna choose what I’m gonna put my time and energy into, well, I also have a clear sense of what I’m passionate about. Certain artists that really shaped my palette, my taste, my career, and people that I actually enjoy working with. And if I’m lucky enough to be in a position to choose who I work with and to define how I project my identity in a sense, right? Like if I’m putting scratch videos on my Instagram, if I’m doing a passion project on the SP-1200, that’s just me doubling down on what gets me geeked and what I’m excited about.

And the idea of building monuments for certain movements in the artists and sounds that I’m passionate about, that fits into that lens too. And that fits into that phase of my career of like, alright, DJing’s gone through a whole shift of changes compared to the Stretch and Bobbito era, the era that I come from. And now we can all define what we want to do. Well part of what I love is to pay homage and use my voice, and use my platform, and use even my sort of curator sense to do something like this Cam’ron album where as a fan, I want this album to exist. I wanna have that project to listen to even myself. So I’m just gonna tough it out for forever [laughs]. For however many years it takes to get it to the finish line and stay passionate about every single detail until the last second, into going into the artwork and the marketing and everything. ‘Cause I care about this.

It’s been a trip for me. As this record actually came out, to think not simply how many years we’ve worked on it, but look at what happened to the landscape during those years. It’s changed a lot. It’s interesting how through all the different shapes and forms that the music landscape has taken during those years, as much on the hip-hop side, as on the general DJing side and everything else, there’s a place for a record like this.

Hip-hop is also flooded with collab tapes now, which really wasn’t as common back when you, Cam’ron and Dame started working on Federal Reserve. I’m interested to hear your thoughts on where this fits into the present landscape after working on it for eight years.

A-Trak: When we decided to pull the trigger on releasing the album this year, I got everything mixed again because of how much the hip-hop landscape has changed since the last time that we had a release date for this record. So whether it be, like you mentioned, the concept of producer and rapper collaboration tapes, or even just sample-based hip-hop – there’s a lot more context for this kind of record now than three, four years ago, let alone seven or eight years ago. I definitely have this, ‘never on schedule, but always on time’ feeling about this album where it did come out in a time and place where there’s context for it.

When we started working together, it was just Dame’s vision in a sense. Zooming back to 2014 for a sec – Fool’s Gold Day Off was probably at the biggest scale that it ever reached. The original Rock the Bells was no more, Rolling Loud didn’t exist yet. Even though Fool’s Gold Day Off was always a boutique festival, at the end of the day, we were kind of the only name in town for putting rappers on a festival stage during that time period. And funnily enough, I put AraabMuzik on the festival stage and I was the first to do that. He was managed by Dukedagod who worked with Dipset. After I put AraabMuzik music on Fool’s Gold Day Off, he got a booking agent and next thing you know, he was playing legit festivals in front of 10,000 people. So a lot of rappers were still playing walkthrough performances at clubs – You know the ones with the funny flyers with like some random girl on a flyer and the rapper’s name. And the rapper’s in VIP with a mic doing shoutouts for three songs then picks up a bag of cash.

That was the standard for a hip-hop performance at that point in time. At Fool’s Gold, we’re putting on real shows. Dame was aware of that but I didn’t even realize how aware he was. I’ve known Dame on and off over the years. He was there when I met Kanye way back in the day. I was working on a couple of records just for fun and I thought it would be cool to get a verse from Cam’ron. So I just called Dame to see if I could get a verse from Cam not even sure what their status was, if they were even working together closely at that point in time.

And Dame immediately had this bigger vision where he was like, “Yo, you’ve been doing those Fool’s Gold shows. I saw what you did with AraabMuzik music. Cam should be with that. You guys should do a project. Cam just needs to meet you and you gotta build trust with him. So I’ll connect you guys, I’ll be there the whole time. As long as he gels with you, you guys should just do an EP and then tour it. You put it at your festival.” All of that just off of a phone call with Dame where I was only like, “Hey, can I get a verse?” That’s how the collaboration started. We recorded a couple of songs, announced Federal Reserve, didn’t finish the project, and ever since that point there’s been this sort of demand or anticipation for it.

So what happened?

A-Trak: We both got busy. Cam went on tour, I went on tour. Cam kind of just works when he feels like it, which at this point in life as he should, you know? But there’s a point where we kind of lost his interest. And as he went on tour the next thing you know, I think two years went by and then we got back together two, three years later, Dame kind of got the itch again and rallied both of us up. We had something ready to cut and put out by 2018 and we wanted to sign it on neutral ground ‘cause all of us have our own labels. So we signed to Empire and we were about to put it out around early 2019.

I had mixed the whole album myself, I remember really spending a lot of time thinking about the sound of those beats, how at that point in time mixed sounds had gotten really polished and clean – just engineering in general had come a long way. But that wasn’t the sound that I wanted for Cam’ron. When I would listen to those classic Heatmakerz beats from the Diplomatic Immunity era, there was a slight distortion and this rough-around-the-edges quality that I wanted to keep. You could tell that The Diplomats were putting out tracks that a lot of times weren’t even professionally mixed. They would just get a beat from the producer. record to it, then drop it – not even get the stems or even get it mixed. But there’s something about that roughness that was part of the character of The Diplomats that we all liked.

On some engineering shit, at that point in time when I was finishing the mixes before the pandemic, there wasn’t much current context or even current projects to compare the sped up soul beats with hard east coast drums to. I was just literally referencing 2003 beats, Dame Grease and producers like that. The whole rapper and producer album was starting to happen a bit. I don’t remember exactly the timeline, but the stuff that Freddie Gibbs and Madlib were doing, and then Freddie and Alchemist, things like that were starting to pick up some steam. Going back a couple years prior, of course there was 9 Wonder and Murs – it’s not a new concept, but that became such a thing in the last couple years with what Muggs did and what Alchemist did, of course, the whole Griselda thing.

I think looking at the last couple years as far as sample-based music between what Griselda did, what Alchemist has been doing, Mach-Hommy, and of course Roc Marciano, who I think is the godfather of this whole resurgence of haunting loops, there’s now a lot to compare [U Wasn’t There] to. Now this wasn’t a ‘no drums’ album in the way that the sort of Roc Marci influence and then the Griselda sound became – of course there were hard drums on this, but now there was just more to compare this to. I ended up getting Eddie Sancho to do new mixes on the whole album this year. Then we put it out. I had time to think about this project for many, many years and you know, everything is based on context.

Dame Dash: A-Trak fought for it. Every time we would start, we couldn’t finally just get it out. We didn’t roll it out with videos and we have a lot of assets to promote it, but it’s just, you gotta get Cam when you can get him. So he finally approved it, I guess. And A-Trak had the deals all set up and honestly, this is the way I like to do music where I don’t have to be the administrator. I like to curate and be a part of the chemistry of the art and bring people together. I don’t like to deal with the business ‘cause people get on my nerves. A-Trak and his crew did all the shit I hate to do and now we could just sit back and see what it do, in a very organic way, which is always cooler anyway. Sometimes no strategy is the best strategy.

It is kind of strange that people now talk about marketing and album rollouts as an extension of the artform.

Dame Dash: I don’t fuck with the industry. Like, if someone has an industry, it’s only gonna behoove the people that created it, not the people that make money working for it or get exploited. So you have to make your own industry and you have to make your own protocol for the way you monetize your stuff. So if you put your destiny in the control of another industry, then you’re saying, you guys make money off it first and then I get what’s left. That doesn’t behoove me. The only way is to stay creative, to stay inspired and to stay making cool shit. As long as you’re inspired by culture and you continue to create… You get so sick of working with the industry that you quit the art. I never quit the art, I quit the industry… I am artist first – always have been, which is why I don’t do shit for money. I do shit for art, which is why I’m the worst businessman, but I’m the best artist.

Dame, I want to get your take. What was it about A-Trak that made you want to scrap the initial idea of a quick feature and instead want to work on a full EP with Cam’ron?

Dame Dash: Well, I was in London with A-Trak when he was like 15 and I tried to put him with Samantha Ronson and I just happened to have Kanye with me and he was like, “Nah, I think I’ll go work with Kanye.” I was like, either way, it’s Roc-A-Fella, I don’t care. So I always kind of knew him. And then I liked what he was doing [with Fool’s Gold Records] you know – I’m into that indie, DIY, cool kid kind of thing. And he had that kind of lifestyle, pause, movement. So when he called me, I was always looking at what he was doing as cool regardless – the festivals and the artists that he aligns himself with and he does the rock and the house. Everything he does, it’s a good collaborative, cool thing.

So when he called, I was like, “Nah, fuck a single, let’s do a project.” At the time, I don’t think Cam really had an understanding for a long time of how the rest of the world looked at him. When I was doing DD172, what I learned was the indie white kids were obsessed with Cam’ron back in the day. I would do things like take him or Jim Jones to places where they would never go – some place in Brooklyn in a warehouse and have them perform and they would just – it was ridiculous. So I knew that would be a good project for that crowd and that would also bring Cam’ron into the festival crowd. The way Dipset used to do their shows, I always knew it wasn’t sustainable.

It would be like, yo, you can’t have a hundred people on the stage and you’re performing over a track. That’s not festival shit. So I never saw Cam really get the benefit of doing festivals like the rockstar that I had viewed him to be. And I thought that that project would also get him into the festivals as well. Above him being a hip-hop legend, I always looked at him as almost a rockstar, an international sort of a personality that the rest of the world, other than outside of hip-hop… I never thought he hit that peak. And I never give up. So I just felt like this is that one more shot to get Cam where I want him to go. I don’t want Cam to be an artist that’s only performing “Oh Boy” 20 years later. He’s an artist that should be performing current records.

Working with Cam can be challenging because he’s a true artist that doesn’t do too much for money. He does things for whatever makes him feel good, which can inconvenience everyone that he’s working with. So working with Cam is like lightning in a bottle… being able to get ’em someplace at a time, capture and get everything we need, that in itself was an art. It’s hard sometimes to schedule greatness… And I remember A-Trak does not take no for an answer and that’s why I like him. He’s a little tough motherfucker and he stands behind what he believes in. You’re not gonna push him over. If he wants something done, he’s aggressive about it.

U Wasn’t There is a testament to not just you and Cam’s decades of being relevant, but also the fact that you’re still paying attention to where hip-hop is presently to make this project right at home in 2022 in a way that could have been different in 2019 or even 2014…

A-Trak: It’s like a sculpture man – you have your sculpture that’s practically done for a long time where you’re looking at it and you’re like, “I can’t quite tell what it’s missing, but it’s almost there. Let me walk away from it for a second, come back to it.” And when you come back then you’re like, “Oh no, I know it needs to have this different kind of sheen actually, or the edges need to be rounded off differently.” You need to put little touches on it, and a lot of what I did over the last couple of years was just coming back to it with clarity and the current context to be like, “Oh no, no, no, we need to actually take this form.” Truthfully, the last iteration of the project before the pandemic that almost came out, there was a point in time where a couple songs got removed from the record and then this year when we got back on the same page and decided to put the record out, I was able to put most of it back together.

The whole Federal Reserve project was always meant to be an EP. It just so happens that we recorded this amount of material over time and when I was able to tally everything up this year once and for all, did the new mixes and kind of looked at everything, it was nine songs – we didn’t even necessarily set up to make an album. But the more it came together, especially once we started having Dame’s skits, I got into album mode in the wrap-up period.

The instrumental curation, the sequencing, the skits – it’s clear that you’re not only a fan but an expert of the different eras of Dipset and Cam’ron lore. Do you remember the first time you heard a Cam verse?

A-Trak: Man, the first time I heard Cam was probably 357, which I think came out of ‘97, which is a trip ‘cause our careers have had the same timeline. My career took off when I won the DMC battle in ‘97. It’s just that he operated on the major label scale early on, whereas I kind of of slowly built my career up. I remember going to New York with my brother [Dave 1] around those years and just buying mixtapes from the bootleggers. There was a point where once Cam’ron was hot and he was on those freestyles, he was doing joints with DMX and on the same timeframe as when The Lox were blowing up. Cam was doing the fast flow, like right before “Horse & Carriage” and I remember really just really being into him and the style beats that he had.

I believe Dame Grease was doing at least some of those beats, where it was kind of the Jiggy era, but the shit that Cam and DMX were rapping on still had sampled drums and these little chopped up stabs, so it still had grit. It wasn’t full [Korg] Triton, which I had a little bit of a hard time with the Triton sound in the beginning. I was really a purist, which, you know, I was wrong, but at that point in time I needed some sort of grit in the beats that I was hearing. And I liked that the beats that Cam rapped on had that. But his flows were crazy impressive. Obviously he slowed down afterwards, but I was a fan right from then.

At that point in time back up in Montreal, my brother was managing a record shop. It was one of the few hip-hop record stores in the city and he was the buyer also. So he would order vinyl and Cam’s first album, Confessions of Fire stayed on those racks for quite a while. Sadly, Montreal was not really buying that LP. So his record cover is a record I saw for a long time on that wall. No disrespect of course. I was familiar right from the start and stayed a fan of the many evolutions of Cam’ron. On S.D.E. he had “Losin’ Weight” which was crazy and I was a huge Prodigy fan.

In 2002, 2003, Cam emerged with The Diplomat sound that we now know – kind of slows down the flow, gets a little more absurd with the lyrics. The persona takes shape as The Diplomats are putting out mixtapes. It was 2005 or so when I really wanted to make a song with them but I couldn’t even get to Cam in those years. But a friend of mine, through a connection with Roc Raida, rest in peace, who was one of my mentors as a battle DJ, connected me with a dude who helped me get JR Writer, Hell Rell and 40 Cal on a song. So I made a song with them, who were sort of like the junior team of The Diplomats called “Don’t Fool With the Dips.” So I’ve been trying to work with these guys for a long time [laughs].

This project almost didn’t see the light of day, so what about Cam’ron kept you coming back for nearly a decade to get U Wasn’t There across the finish line?

Dame Dash: It was like capturing friendship and capturing fun, which is the way art should be. For me, when someone just has subject matter and they write about it and they’re strategic, that’s not art. That’s more business. But when you create a vibe and just catch whatever comes from it, that’s art. But you have to capture the essence of it. And that’s every single thing creatively that I try to do. I don’t try to monetize anything contrived. What I try to do is capture authentic moments and put ’em in different vibrations.

The interaction between Cam’ron and A-Trak is interesting because A-Trak’s always trying to find a way to communicate with Cam’ron without offending him and that used to have me cracking up. I think we all had our different moments that triggered enjoyment, pause, from the whole [time]. But at the end of the day, just hanging out and having fun in environments where it was just us without the bullshit of other people’s energy.

A-Trak: As far as why I’d wanna work with him, I was just always a fan. He’s one of my favorites – his verse on “The Roc” with Memphis Bleek and Beanie Sigel is one of my favorite verses by anyone ever. I was always more than down to work with him period. And especially by the time we started Fool’s Gold and by the time I was shaping my place in the New York landscape and in New York culture, he had emerged as this Tumblr-era iconic figure too. I moved to New York, I was passionate about New York, things that were part of the New York iconography were important to me. And Cam was just one of those ultimate figures. You put ’em up there with Ghostface and in the light where it’s just these truly one of one artists whose lyrics are practically on some Dada levels.

Once we started working together, it was interesting to observe him too ‘cause clearly this is someone who has been rapping since he was a teenager and who does this in his sleep. He has a studio at his crib in Jersey. So that first summer that we were recording together, it would basically be me and Dame linking up with Cam and going to his crib in Jersey. He’s got an engineer at the house and we would just record on his setup. He doesn’t do a hell of a lot of takes. He writes the verse pretty fast, does the first take. And if there’s a couple words that don’t come out just right, he’s gonna layer it with a bunch of ad libs and backups anyways, so they get fixed in the stacks. It comes together pretty fast. He’s not the type of artist that I saw, at least with me, who will really second guess something once it’s recorded or come back to a song and be like, “Oh, well maybe we should change this verse or that hook.” It was more about capturing a moment in time. I would play him beats and if he fucked with something, he would write to it and record to it.

I think a lot of [the songs] were also the product of what was going on in the room. And the thing is, Cam and Dame hadn’t spent as much time together in the years prior to that. They each had their respective careers and they each had become legitimate businessmen. Cam’ron, outside of rapping, is an excellent businessman. He knows how to read his contracts too – he’s really on top of his shit. So it felt like getting to the rap was almost like bringing him back to the thing that he does in his sleep.

Cam and Dame would be catching up and I would sort of be the fly on the wall for that. I think that having a sort of innocence in the room and having a lot of reminiscing and a lot of just cracking jokes between people who have been cracking jokes at each other since they were teenagers laid a certain tone for a lot of the recording sessions. I was realizing that part of my role as a producer too is not only to make the beats or choose the beats or rework the beats, but also to be mindful of the actual vibe of the room as well – to make sure that everybody’s in the best mindset to be recording.

Dame helped a lot in that respect too. By that point in time I was mostly producing house music, but hip-hop is always my first love, my first passion. So I’m always excited to make music, but I wasn’t exactly sitting on 50 beats myself. But I have a bunch of friends who are great producers. To me, a beat for Cam’ron and Dipset needs to be produced in a certain way. So I would be looking for rough beats that people around me had started where I would hear something in the sample or in the sort of cadence of the drums. A lot of times I was looking for samples that felt like I could bring it to a Dipset place.

Once I had stems and I would record Cam over that rough beat, then I would rework the beat, especially the drums and basslines to give it that sort of the feeling that I was describing when I was listening to a lot of Heatmakerz, Dame Grease, Just Blaze.

Then there was another step of getting samples replayed, working with the people doing the replays and a lot of times we would replay them in a different way so that it’s no longer a clearance issue. That sometimes brought the beats to a whole new place. A track like “Think Boy” was an entirely different beat when it first started. And then I recorded the vocals, basically remixed it, put a whole other beat to it, and there was still a sample in it so I removed that sample entirely. So by the end there was nothing in common between the original beat, the new beat, but it’s the process of imagining a beat that those flows would sit well on. And that would also kind of tick a box in the album that I’m trying to shape. I was always a fan of reggae beat Cam’ron, ever since “What Means The World To You.” “Dipset Acrylics” ticked that box but “Think Boy” was a new composition with DJ Khalil and some of his musicians where I chose to bring it in that direction.

Was there anything that A-Trak or Cam’ron did creatively that surprised you on this record after working with them for so long?

Dame Dash: Yeah, there were a couple of records that I was like, damn Cam can still really rap. To me, Cam is almost a bit different than he was before. I guess it’s more evolved. Back then, it was evolved but he still had the recklessness of when he was young. So it was like an evolved version with the recklessness still, like a glimpse of the old Cam but with almost better rap skills. I always loved that A-Trak has a pure understanding of the Dipset sensibility of the beat and the essence of it. He knew what beats to bring and he knew the direction of the records he wanted. No one was trying to make a pop record or a hit record. We were just trying to make authentic, real records. I liked that he was fighting for that and that’s why I fuck with him, pause. That part almost wasn’t surprising.

It was just sometimes when you suspect something and then you see it. I suspected A-Trak don’t take no shit, but he really don’t – I saw it. He stood up to me and Cam several times, he’s not a pushover. To actually see it’s still a little surprising – I still grin when he’s fighting back with me, you know what I’m saying? He never goes backwards, but when he feels something, he stands behind it no matter what. So I like all that.

Between reggae beat Cam’ron, reflective ‘respect my resume’ Cam, and some Easter Eggs on the different eras of what could’ve ultimately been Federal Reserve, there’s something for everyone. What made you kick this project off by revisiting Purple Haze 2’s “This My City” with a chipmunk soul and gospel flip?

A-Trak: It wasn’t remade – that version was done first. That was originally a beat from Thelonious Martin that I played for Cam. The verse had already been written and you could tell he thought, “Oh, this is a beat I can do this verse on.” We recorded it then I went and did my thing to it, took out the drums, put in new drums, reworked the sample, all that kind of stuff. Somewhere along the way Cam was working on Purple Haze 2 and he put that verse on it. I was like, damn, that was my album opener. Time passed and you know, it was no longer a question of having to choose one or the other. That was one of the benefits of having a little bit of time pass where we could still use it.

There were a couple of last minute switches. Even as the album was delivered, to be honest, “Ghetto Prophets” was gonna be the lead single and we had a different hook. We had to switch it, switch the guests kind of at the last minute. There were a couple of issues with clearances, so as we were getting ready to drop “Ghetto Prophets” as tentatively the first single, we realized that we didn’t have a hook on that song anymore. We were able to get Conway literally at the last second, but in the meantime we had to go to Plan B for a lead single and that’s where “All I Really Wanted” came in.So some of that was just bob and weaving through the last couple of obstacles of getting this album ready to release in the last month.

Up until literally a week before release, we had to switch a vocal on another song, too. As much as this record’s been in the vault for a while there were twists and turns until the very last second [laughs]. But once we got to the conversation of choosing “All I Really Wanted” as a first single, it was a, “Oh wait, that makes perfect sense” moment. It shows Cam’ron in this reflective place that he’s in on this album, which feels different from his other projects. I even have scratches at the end. It shows the collaboration between him and I. So it actually felt like a perfect choice and I’m really glad that we led with that.

We’ve talked a lot about context with this album release, this whole concept of timelessness – never late, but always on time. And we get to see Cam’ron at his most reflective yet, looking back on a 30 year career in hip-hop with these iconic moments: O’Reilly Factor, pink fur, Anderson Cooper. How much did Cam’s present influence your decisions on the project?

A-Trak: You know, I’m not in his head, so I don’t even know exactly what Cam was thinking about. And now that I think about it, “What You Do” was also a beat that I switched afterwards where I literally remixed it with the help of !llmind and some of his co-producers. But when we first recorded it, I just remember that he heard a beat and had an idea right away. Cam didn’t even make a big fuss about it.

I do think the fact that Dame was there with us when we made these records, they were reflecting on their lives a lot in general ‘cause they were reconnecting. There were a couple of other people there, so they were commanding the room and making everybody else laugh by telling stories in between recording songs. Man, they were just laughing and reminiscing and I really feel that it seeped its way into some of Cam’s writing.

I was surprised that he asked me to pitch down a vocal cause you know, you don’t really hear Cam’ron all over screwed up vocals. So he laid down “What You Do” and the way he wove his lines around it – we were just cracking up. It was recorded pretty fast. It seemed like the easiest thing for him and clearly he’s aware of his own iconography.

What was it like sequencing this eight year odyssey with your brother, Dave 1?

A-Trak: He and I are co-executive producers on this project, and we’re both longtime Cam’ron fans. So we would think about, well, okay, is there a style of Cam’ron or Dipset beat that we don’t have that would be good on this project? I mentioned “What Means The World To You” earlier, but even The Heatmakerz were sampling reggae too – “Dipset Anthem” is a reggae sample. To me it was one of the things that always worked well with Dipset beats that I wanted to try.

It was that simple – it’s just nerding out over production styles. It gets even more nerdy than that, literally down to the choice of every snare, down to the styles of hi-hats and quantizing styles. There is such an aesthetic to Dipset. I obviously tried to not replicate it ‘cause I’m not trying to only make a retro album, and I’m not trying to out-Heatmakerz The Heatmakerz or out-Just Blaze Just Blaze. But we understood the lines within which we color and then made our version of that, and I like that exercise.

I don’t think [Dave 1] and I disagreed on anything with this record. He would help me keep track of the big picture and if I was in the weeds of recording with Cam until 3:00 AM and just trying to come home with files that I knew I could fix up later… he and I would share a folder and just listen and he’d be like, “Yo, he killed it on this one. You’re gonna need to rework that beat a little bit, but you have what you need.” But then he would also be like, “Man, if only you could get this kind of song…” We would workshop the ideas and then the next time that I was in with Cam, I would try to steer it in some sort of direction and then I would come home with files and rework.

It took both of us back to fan mode and listener mode. Dave had just moved to New York in like 2002 or so, before I did ‘cause he went to Columbia, and so he was there when Dipset tapes were coming out and I would come down and visit him and we would just rock out to those tapes in those years. So fast forward 15 years later and I’m making a record with the head of that crew. We were transported back to those years when we were jamming to those records the first time around

Dame, did you ever think that in 2022 that you and Cam would still have a foothold in the culture, even with how young and how ever-changing hip-hop is? That you’d be able to release a record like this and still get a response?

Dame Dash: If you take this shit too seriously then you’ll always be like… anxiety. But I guess if it was what was paying my bills, I might approach it differently. But that’s what’s so genuine about it is it’s more like, this is icing on the cake. We already did all the business, now let’s just do shit. This project was pure fun for me, purely so I could get back on the stage with Cam so we could still fuck around, pause.

I’m not in the music business anymore but I have enough legendary friends, brothers that whenever I get inspired, ‘cause I keep a studio, I keep a live band, I have the ability to capture a moment, a freestyle, anything… because the coolest shit is never contrived… Music after a very short time for me became something ancillary. It became a vertical to everything else that I was doing. So would I be able to just put a record out this old and it still be hard to the young kids? Pause. Nah, I am surprised. I’m actually really happy about that.

When we started working together, it was just Dame’s vision in a sense. Zooming back to 2014 for a sec – Fool’s Gold Day Off was probably at the biggest scale that it ever reached. The original Rock the Bells was no more, Rolling Loud didn’t exist yet. Even though Fool’s Gold Day Off was always a boutique festival, at the end of the day, we were kind of the only name in town for putting rappers on a festival stage during that time period. And funnily enough, I put AraabMuzik on the festival stage and I was the first to do that. He was managed by Dukedagod who worked with Dipset. After I put AraabMuzik music on Fool’s Gold Day Off, he got a booking agent and next thing you know, he was playing legit festivals in front of 10,000 people. So a lot of rappers were still playing walkthrough performances at clubs – You know the ones with the funny flyers with like some random girl on a flyer and the rapper’s name. And the rapper’s in VIP with a mic doing shoutouts for three songs then picks up a bag of cash.

That was the standard for a hip-hop performance at that point in time. At Fool’s Gold, we’re putting on real shows. Dame was aware of that but I didn’t even realize how aware he was. I’ve known Dame on and off over the years. He was there when I met Kanye way back in the day. I was working on a couple of records just for fun and I thought it would be cool to get a verse from Cam’ron. So I just called Dame to see if I could get a verse from Cam not even sure what their status was, if they were even working together closely at that point in time.