Son Raw‘s got more flips than lucha libre.

As with a great many things in hip-hop, the end was heralded by Vibe Magazine. The Roots’ ?uestlove had spent the late 90s working out of Electric Lady Studios in NYC, alongside co-conspirators D’Angelo, Jay Dee (later Dilla), James Poyser and assorted artists; recording music, conceptualizing albums, and generally collaborating, as musicians are want to do. The communal atmosphere was warm, the door policy loose, and the early fruits of their labor Grammy winning (1999’s Things Fall Apart. By the time Vibe Magazine came sniffing around for a story, that triumph had snowballed into D’Angelo’s generational masterpiece Voodoo, and Common’s Like Water For Chocolate, a commercial and artistic breakthrough. When Vibe’s feature on the now Soulquarian Collective hit the streets, Erykah Badu’s sophomore effort Mama’s Gun was imminent and set to be another feather in the collective’s cap.

These were well-deserved wins for a group of artists that had been on the outside looking in. As gangsta rap ballooned to account for an increasingly dominant slice of hip-hop’s market share, a backlash began to brew, lamenting the culture’s turn towards shiny, synthesized beats and materialistic rhymes. In R&B, the complaints went back even further, with some purists deriding everything post-1980 except Prince. In truth, the charts were more balanced than they seemed – D’Angelo and Badu had both released debut albums to critical acclaim and the “Neo-Soul” genre tag had its devotees.

As an aesthetic, however, earthy, soulful and smart played the backseat to “Money Cash, Hoes.” In this cultural climate, Vibe’s Soulquarian feature must have felt like the Black alternative time to shine, not just for the core Soulquarians, but also names like Q-Tip, Mos Def, Talib Kweli, and Bilal, and for any listeners who bristled at Black music’s mainstream representation.

Or at least, it should have been. As ?uestlove notes in his biography Mo Meta Blues, almost everyone had a problem with Vibe’s reporting. It made ?uestlove look like a ring leader, some members weren’t Aquarius’ at all, and quite a few chafed at the artistic box they were increasingly becoming trapped in. Due to a mix of personal and artistic differences, the collective would fracture apart over the next several years, with Common, Talib Kweli, The Roots, and Mos Def all dropping contrarian curveballs to free themselves from the expectations of Rhodes chords and grown man vibes, while D’Angelo and Badu made themselves increasingly sparse. The dream was over, and all we had left were Voodoo, Like Water For Chocolate, and Mama’s Gun.

(Well, and Things Fall Apart, which ?uestlove considers as part of the same run as D’Angelo and Common’s albums — considering Mama’s Gun a later release alongside Common’s Electric Circus. Plus Slum Village’s Fantastic Vol. 2, which was floating around since 1998 but only saw official release in 2000. But for the sake of this column, we’re considering the three records that dropped that year and that hadn’t been bootlegged to death. Besides, Electric Circus still sucks.[ed. note: no])

***

First came Voodoo, an album that could easily take up this entire column on its own, and the type of singular, one of a kind classic that makes music critics and recording nerds alike feel weak at the knees. D’Angelo had already established himself as a leading light in neo-soul’s ascendance with his debut Brown Sugar, at once sensitive and masculine, with an aesthetic that looked towards R&B’s earthy golden age through a hip-hop lens. By 1998, he began working on his sophomore effort at Electric Lady Studios as part of the aforementioned collective, slowly assembling, deconstructing, and rebuilding his sophomore album with the kind of time, money, equipment and expertise only available to top major label artists during boom times.

This was, to put it mildly, unusual for R&B circa 2000: the genre’s brightest lights including R Kelly, Dru Hill, Destiny’s Child, Alliyah, Mary J Blige, et all, worked fast and kept an ear towards the charts in a futuristic pop arms race. Quarantining one’s self for 2 years alongside the drummer for an alt-rap band and his buddies was the sort of thing that made record execs nervous. A bad case of writer’s block didn’t help ease their fears, but the birth of his son, along with the creative fuel provided by his collaborators, eventually re-lit the spark.

Voodoo is one of the sole albums in this column whose sound I’m hesitant to describe. Many many pieces and a whole 33 1/3rd book have been written about it, but Voodoo’s sound remains evasive, and few writers manage to capture exactly what makes the album so special. There won’t ever be a Youtube tutorial showing budding musicians how to recreate its magic, no matter how much they bite Dilla’s drums. It’s the result of a lifetime soaking up Black music in the church and on record, with several generation’s pain, joy and creativity providing the foundation. It’s a masterpiece by the heir to Prince and Marvin’s thrones as channeled through a record nerd’s fever dreams. It’s the sound of a multi-million dollar studio’s warmth and tape hiss recording ?uestlove doing his best sloppy Jay Dee impression on the drums.

(This is as good a time as any to mention that Jay Dee somehow doesn’t have a single official production credit on Voodoo, despite being a clear influence, a known entity at the sessions, and a core member of the Soulquarian collective. Your guess is as good as mine, although I’m sure a Dilla or D’Angelo super fan will immediately educate us via Twitter once this is posted.)

Perhaps Voodoo is so singular because it nimbly dodges not only its own epoch’s commercial concerns, but also those of the era it looked back towards. While soul legends like Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder and Curtis Mayfield blessed listeners with their fare share of un-commercial left turns, Voodoo would have stuck out like a sore thumb next smash hits like Superfly, Talking Book or Let’s Get It On. It’s too earthy, its feet planted deeply in the same southern soil that spawned the blues and New Orleans R&B, but it’s just as enraptured by the possibilities of sample-based hip-hop production. Sly Stone’s There’s A Riot Goin On is a clear stylistic antecedent, but Voodoo has none of that album’s debauchery and desperation – that would come later. It’s sexy, but not photoshoot sexy, if sounds smelled, Voodoo would be funky in every sense of the word.

Above all else, it was defiantly, and poignantly, not to be categorized next to the Pop-R&B dominating American airwaves at the dawn of the millennium. The liner notes are by poet Saul Williams, ?uestlove wrote an essay about its importance, and D’Angelo himself bemoaned the state of R&B and positioned Voodoo as a reaction to its commercial excess, club focus, and disconnect from Black music’s roots. The album was recorded on analogue equipment with minimal overdubs (D’Angelo’s multi-tracked vocals aside) or digital trickery. This was serious music, yet none of this stopped the album from becoming a commercial juggernaut.

The video to “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” played a major part in that. An artful, black & white collage of D’Angelo in the nude, it became the flashpoint for the album’s commercial success, driving a generation of young women (and men) to hysteria, particularly during Voodoo’s smash hit tour, where the reactions of female fans rivaled Beatlemania.

Suddenly, D’Angelo’s serious corrective to R&B was caught in the very pop machinery it had so painstakingly tried to denounce.

I’d like to think things would play out differently today. Struggles with mental health are more normalized, and the dehumanizing effects of the media is far more understood in an era where we all carry tiny television cameras/tracking devices on our person at all times. Yet I don’t think anything prepares a deeply introverted, spiritually-minded, record nerd for what D’Angelo went through in the aftermath of Voodoo. Facing a crisis of confidence and recognition for all of the wrong things, D’Angelo vanished into a decade and a half long weekend, emerging mostly via disheartening news stories and the occasional missive from ?uestlove. Voodoo meanwhile, once the sexual hysteria died down, became recognized as an unimpeachable 5 star classic among R&B experts, hip hop/beat heads, and even the type of rock critics that gate kept the pop music canon throughout the 2000s. It’s a perfect record that belongs less to the year this column is examining than it does to some infinite plane beyond time itself, one probably only accessible to practitioners of actual voodoo.

***

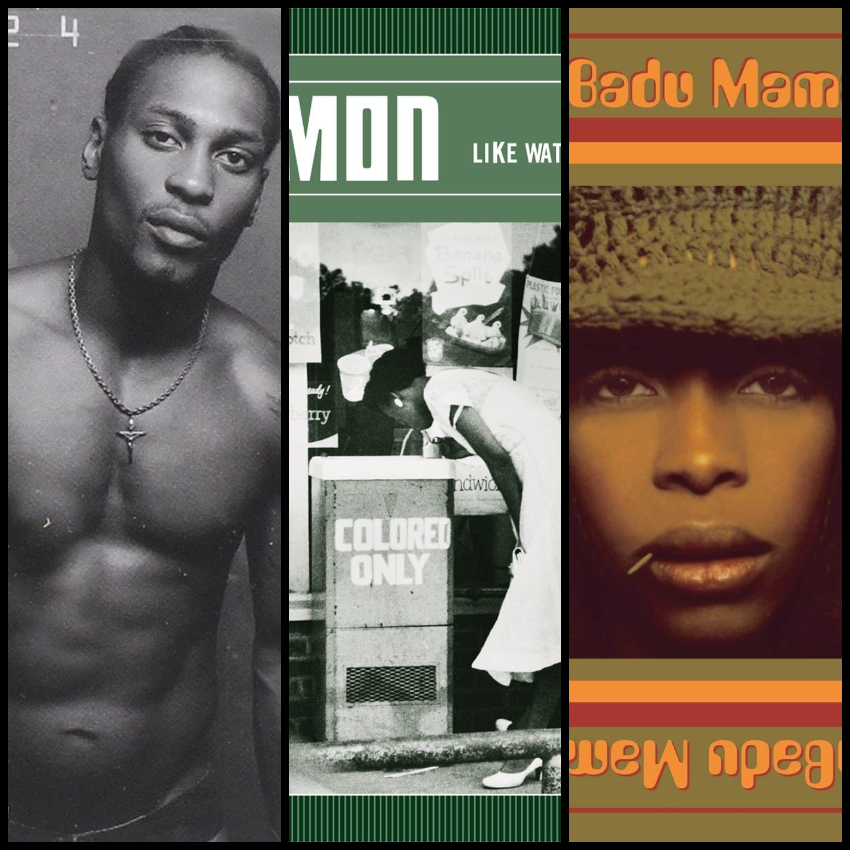

Common’s Like Water For Chocolate conversely, is a far more street level experience, even if it stood apart from its millennial competition in both aesthetics and content. By the time he’d embarked on his 4th album, Common was an industry veteran with mixed success. His debut Can I Borrow A Dollar arrived at the riggedy-wrong time, just as its Native Tongues style eclecticism and Das EFX inflected flows fell out of fashion for G-Funk’s slow rolling sneer. Despite an Unsigned Hype cosign in The Source, that might have been the end of it, bar an awkward turn towards the hardcore like most of his peers, but instead, Resurrection, his sophomore album, captured the zeitgeist of a generation of hip-hop kids transitioning to adulthood with all of its grey areas, nuances, and unsatisfying ambiguity. Standing tall next to rap bildungsroman releases like Nas’ Illmatic and O.C’s Word Life, it helped usher in seriousness and introspection to a genre still high off teenage giddiness, without being as weird and out there as say, Freestyle Fellowship.

Commercially however, it did just well enough as to keep Common working, and when its follow up One Day It’ll All Make Sense failed to do chart significantly better, it was clear he needed a change of pace and scenery.

Signing to MCA, hooking up with Erykah Badu, and rocking a more… let’s call it bohemian wardrobe, Common was ready to move past the backpack label in a rapidly consolidating music industry. First however, he needed a sound to match both his new look and the burgeoning Afrocentric consciousness he shared with his new friends and lovers: enter Jay Dee. As the primary or sole producer on 9 of the album’s 16 tracks and a contributor to 2 more, the future Dilla became the album’s driving musical force, pushing Common out of his comfort zone while still grounding him in crunchy, Midwestern soul.

At first glance, Like Water For Chocolate’s pillowy Rhodes lines and finger snap snares aligned Common with neo-soul’s adult sophistication and classy musical signifiers, but deeper listens reveal the Detroit grit underneath the newsboy cap. The bass bumps and lands at odd intervals, the drums are loose and unpredictable long before turning off the quantize feature on an MPC became a trope, and for all the snickers about incense and daishikis, Common was never better at balancing romance, introspection, poetry and realism as he was on Like Water For Chocolate.

Crucially, he eased any digressions into unknown territory by delivering a slate of strong singles. “The 6th Sense” came courtesy of DJ Premier, a last minute addition to the album that shored up purist support and guaranteed mix show play in an era where Gang Starr were underground kings and everyone from Jay-Z to Canibus was hitting Premo up for beats. It’s a clear outlier on the album, a boom bap palette cleanser in the middle of a project more interested what comes next, but it drew in newcomers and kept Common’s current fans happy.

The real story however, was “The Light,” a Jay Dee-produced love letter to Erykah Badu that flipped blue-eyed soul singer Bobby Caldwell and The Detroit Emeralds into a mid tempo retort to songs like “Hot Girl” or “Is That Your Bitch.” Like D’Angelo, this is where Common hit pay dirt – by offering a sexy yet sophisticated alternative for college girls and bohemians who grew up on hip-hop but who were getting turned off by the genre’s increasing crudeness and materialism. He may not have had D’Angelo’s abs, but in sweet talking a generation of young women, Common found his audience, one that pushed Like Water For Chocolate past gold and convinced MCA to send him back to the studio to remix deep cut “Geto Heaven” into a driving, Philly-soul inspired single.

By the time the album roll out had run its course, Common was a genuine star. Not a superstar, but big enough that 3 years later, Jay-Z would claim he’d want to rhyme like him, if given better financial incentives.

Like Water For Chocolate is a mess of contradictions. It’s an intentional move away from Common’s backpacker past, even as its Jay Dee-produced beats redefined underground rap tastes for a generation. It’s sensitive and corny – a lot about Common is corny – but also grounded in real life experiences from Chicago to Detroit to NYC. It’s the 2nd of three classics by an emcee who constantly gets clowned on, yet also manages to punch above his weight, more often than not, despite rocking some of the worst fits in rap history. It isn’t quite the transcendental, post-genre masterpiece that Voodoo is understood to be, but by not rocketing to timeless status, it’s become a definitive statement of alternative rap’s strong suits in an era that was all about newer, shinier and faster forms of hip-hop.

Common the actor and Obama-era spokesperson doesn’t exist without it, but listening to this album again, I actually think it’s worth it.

Finally, we come to Erykah Badu’s Mama’s Gun, the final Soulquarian classic of the year and befitting the artist’s ineffable cool, seemingly the least drama free, with no poorly executed stylistic shifts or vanishing acts left in its wake. That doesn’t make for a dull album however, far from it. By Mama’s Gun’s October 2000 release, the neo-soul sound was well established, with post-Dilla drum programming and Rhodes chords rapidly becoming an easy shorthand for sophisticated Black music that stood in opposition to your standard BET programming. The formula was ripe for a shake up, and shake it up Badu did on the album’s opener: “Penitentiary Philosophy.”

A psychedelic rock number owing more to Electric Lady Studios’ founder Jimi Hendrix than anything on radio at the turn of century, alternative or not. The song is a tightrope act, simultaneously grounded in The Soulquarian ethos of updating classic soul, while nimbly dodging accusations of boho easy listening and boldly proclaiming Mama’s Gun to be its own thing. Grammy nominated second single “Didn’t Cha Know” played a similar trick, with Dilla looping up an unintuitive slice of jazz group Tarika Blue’s “Dreamflower” – Badu’s selection – and nudging it into a radio ready time signature. Here again, the soul remains, but the sound closes the book on Fantastic Vol. 2 and Like Water For Chocolate in favor of new vistas, and even when the classic Jay Dee drums do pop up on tracks like ‘My Life,’’ they’re in service of brighter, sunnier sounds.

It all adds up to a soul album full stop, as opposed to one made by a hip-hop kid emulating her parents’ records, and this confidence and maturity is just as present in Badu’s vocals and lyrics. Light years away from her then-current public perception as a mysterious temptress that lured rappers towards singing, veganism, and thrift shops, Mama’s Gun paints Badu as strong but sensual, serious but sarcastic, and sexy but spiritual all at once. She’s less tortured and less conflicted than D’Angelo, which denies Mama’s Gun the kind of gravitas that gets Voodoo placed on all-time lists, but her album more than makes up for that by being genuinely fun.

If the knock against the Soulquarian output is that it was woke music avant la lettre, the equivalent of a big plate of a steamed vegetables, Mama’s Gun felt like defiant proof of the opposite, poppy without being synthesized, slinky and sexual without feeling cheap or put on. Even “In Love With You,” the Stephen Marley duet full of acoustic guitar that lands perilously close to Ms. Lauren Hill territory, feels earned and segues into “Bag Lady,” which dared to sample Dr. Dre’s ultra misogynist “XXXplosive.” Erykah Badu wasn’t finger wagging at gangsta rap fans, she was jacking their beats and making their heroes sweat.

This combination of confidence and levity allowed Erykah Badu to dodge the missteps and disappearing acts that plagued D’Angelo and Common. Though her sound would continue to evolve on subsequent releases, particularly when Madlib and Sa-Ra were involved, her albums all feel connected, variations on a psychedelic soul sound looser and freer than her peers’. She doesn’t ghost fans like D’Angelo, and she never dropped bricks like Common, — she’s still bewitching rappers long after neo-soul hit middle age and started sounding like its parents.

As for Mama’s Gun, it probably won’t go down as Badu’s definitive work, Baduizm completely shifted R&B’s trajectory and New Amerykah (particularly Part 1) is among the finest album length encapsulations of the magic that emerged out of Los Angeles’ beat scene, post-Jaylib. Yet, it still contains some of Erykah Badu’s most beloved singles and it kept her career on track and her fans happy just as The Soulquarians were in the process of blowing up their sound and their collective.

***

That explosive dissolution points to the high and low points of the Soulquarian experiment. On the plus side, artists like D’Angelo, Common, Badu and The Roots co-opted a major label machine geared towards fast-fashion rap to spread newer, more diverse representations of Black life and artistry through radio waves, cable TV, and big box record stores. Though The Soulquarians were oft compared to the Native Tongues, they emerged in a radically different environment, one where hip-hop was more established and business-minded, and the genre’s focus had expanded from teens to include young adults. The collective’s Y2K output went head to head with the shiniest of suits and held its own, inspiring a generation of artists and a community that’s still around to this day.

On the other hand, the group’s implosion is a warning about how money and fame can get in the way of creativity, and showed that just because an artist escapes one box, it doesn’t mean they won’t immediately get put in another. Earth tones and thrift-wear might be an alternative aesthetic, but it’s still an aesthetic and the major labels tried to keep their artists simple and easily branded, at the expense of artistic growth. Within a few years, a young producer/rapper named Kanye West would find a way to check all of these boxes, bringing Common along for the ride, but Jay Dee would continue to struggle with the major label system, delivering his final few releases independently.

Ultimately, the Soulquarian legacy highlights what happens when artists are trusted to create outside of typical constraints, but also how their patrons’ laissez-faire attitude can change on a dime once the prospect of a big payout is on the table. That’s still true today, but thankfully, there are more options than ever to get your music out, even if those options might not pay for Electric Lady Studios.